What is dietary fiber?

Research has shown that fiber is an essential component of every diet and may have many additional benefits for people with a chronic gastrointestinal condition like inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and microscopic colitis.1 Before we dive into understanding the relationship between symptoms of IBD and fiber, let’s take a minute to understand what dietary fiber is.

Fiber: a Complicated, Essential Nutrient

The term “fiber”, in its broadest nutritional sense, refers to carbohydrates and lignins found intact in whole plants that are indigestible by humans. Classically, fiber is described as one of two main varieties: soluble and insoluble. Advances in our understanding of dietary fiber, however, have revealed that fibers possess a wide array of characteristics including solubility, fermentability, and even viscosity.2 Each of these characteristics determines the biological function of the fiber and its unique impacts on our health. Let’s take a closer look:

- Soluble fiber absorbs water in the stomach and small intestine to form a gel-like consistency. Soluble fiber slows digestion; as a result, it can prevent erratic blood sugar spikes and keep you feeling full for longer.

- Examples: pectins, gums, and inulin which are found in foods like citrus fruits, oats, legumes, and some vegetables.

- Insoluble fiber (often referred to as roughage) does not absorb water and instead draws water into the intestinal lumen and adds bulk to stool. This aids the passage of stool through the colon.

- Examples: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin which are found in foods like leafy greens, seeds, whole grains, and vegetable skins.

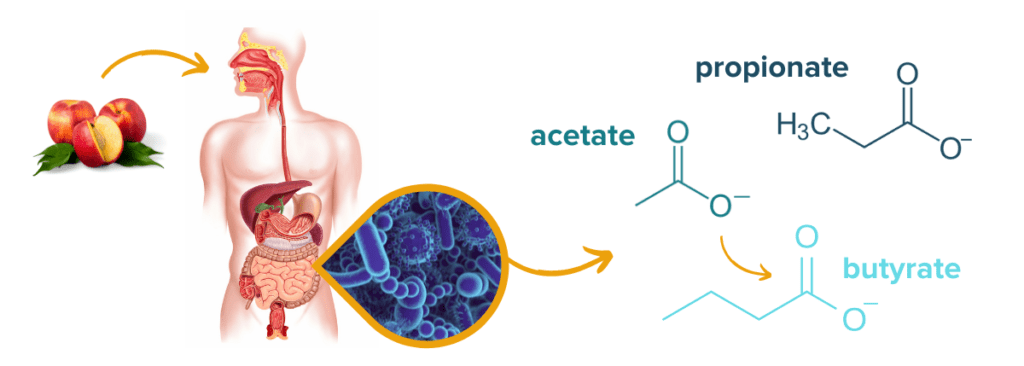

- Fermentable fiber is fiber that is digested by microbes in the colon. These microbes ferment the fiber to produce many different beneficial secondary metabolites like flavonoids and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Fermentation of some fiber types can also produce compounds like sulfurous gasses. You can read more about the benefits of flavonoids in IBD and the benefits of SCFAs in IBD in our other blog posts.

- Examples: arabinoxylans (from oats and legumes), β-glucans (from mushrooms), β-fructans (from bananas and artichokes), pectins (from many fruits, vegetables, and nuts), cellulose (from tough fruit and vegetable skins), and lignans (from seeds like flax) are all at least somewhat fermentable by certain gut microbes

- Non-fermentable fiber, as the name suggests, is fiber that is not readily fermented by microbes in the colon. Many kinds of insoluble fiber are also non-fermentable, though not always.

- Examples: cellulose and lignans are fermentable by some microbes, but are often considered non-fermentable by most.

The various properties of fiber all work together to promote a well-functioning gastrointestinal tract. Consuming a variety of fibers helps food move through the GI tract at an appropriate rate for optimal digestion and nutrient absorption, and improves stool consistency and formation. In addition, fiber contributes to optimal gut health by providing fuel for the human gut microbiome.

Fiber and the Gut Microbiome

The human GI tract is not capable of digesting fiber directly. Instead, the fiber in foods passes along the GI tract undigested to the colon. These undigested fibers become food for gut microbes. Just like humans have preferred sources of food, microbial species have favorite fuel sources and may only be able to digest certain varieties of fiber.1 Feeding microbes their favorite foods may allow certain species to thrive while starving out others.3 Since different fiber types have varying degrees of fermentability and different chemical structures, the pool of metabolites produced following microbial fermentation also varies. This complicated relationship between fiber, the gut microbiome, and the metabolites produced has major implications on human health–especially in gastrointestinal conditions like inflammatory bowel disease.

Learn How Flavonoids From Fiber-Rich Foods Fuel a Healthy Microbiome in IBD

The various properties of fiber all work together to promote a well-functioning gastrointestinal tract. Consuming a variety of fibers helps food move through the GI tract at an appropriate rate for optimal digestion and nutrient absorption, and improves stool consistency and formation. In addition, fiber contributes to optimal gut health by providing fuel for the human gut microbiome.

Fiber and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

A growing wealth of evidence is teaching us that fiber plays an essential role in the development and progression or remission of inflammatory bowel disease.

Read More About the Underlying Causes of IBD

Fiber and the 3 Mechanisms of IBD

In inflammatory bowel disease, a perfect storm of factors triggers an imbalance in the population of gut microbes. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, can lead to the runaway cycle of inflammation and increased intestinal permeability seen in IBD. Diets high in fat and sugar but low in fiber like the Western diet4 have been consistently associated with dysbiosis and IBD risk.5 Indeed, many microbes that frequently have harmful effects prefer fats and sugars as a primary fuel source over fibers. On the other hand, microbes that are known to have more protective and beneficial effects on human health often favor fermentable fibers as their fuel source.1 Some helpful bacteria, for example, metabolize β-fructans (found in foods like artichokes, onions and bananas) into butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Studies have shown in humans that fiber-rich diets increase beneficial microbe diversity and activity. Additionally, reports demonstrate a correlation between inulin consumption, Bifidobacteria activity, and a subsequent increase in the production of butyrate.6 These associations are not absolute, however. Most microbes are capable of metabolizing a wide variety of fuel sources and can adapt to dietary changes. Microbes may be beneficial in some contexts but turn harmful in others. This is especially true for IBD, and more studies are needed to explore the unique relationship between fiber, microbes, and IBD.

Butyrate, along with other SCFAs such as acetate and propionate, are all byproducts of the fermentation of fiber in the gut. These metabolites serve several crucial functions in gut health: they provide the primary fuel source of intestinal colonocytes, regulate gut motility, facilitate communication with the mucosal immune system, and maintain the intestinal barrier by ensuring tight junction integrity.7 Moreover, there is evidence that SCFAs mediate gut inflammation by regulating cytokines involved in the IBD inflammatory response.8,9

Learn How The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis Influences IBD

Additionally, fiber consumption has huge implications for our resident gut microbes. Studies have associated a decrease in fiber intake with both a reduction in bacterial diversity and gut dysbiosis.10,11 Without fiber to feed on, bacteria in our gut can begin eating the protective mucus layer and cause more GI distress.12 Conversely, research shows diets rich in fiber increase the beneficial bacteria in our gut allowing these microbes to out-compete pathogenic bacteria.13 Overall, by the means of fermentation, we see how consuming a balance of healthy fibers addresses all three mechanisms of inflammatory bowel disease: stopping intestinal inflammation, balancing the microbiome, and repairing the gut barrier. How can people with IBD develop the perfect IBD diet with this evidence about the benefits of fiber in mind?

Applying the Evidence to Develop the Best IBD Diet

Historically, people with IBD have been recommended to avoid all fiber. Thankfully, this growing wealth of evidence discussed above has shed light on just how essential fiber is to maintaining a healthy digestive system and the gut microbiome. How did the myth of fiber as a dietary villain for IBDers come about?

The texture and preparation of fiber-rich foods are important to consider for people with IBD. During active flares, the “roughage” found in insoluble fiber can exacerbate symptoms of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.14 But this doesn’t mean that fiber is not a part of the ideal IBD diet.15 A balanced variety of fibers is still essential for gut health, and avoiding fiber altogether during a flare can ultimately worsen symptoms of IBD by promoting dysbiosis (which subsequently worsens inflammation). To fuel a healthy gut microbiome and prevent symptom exacerbation from fiber, foods rich in soluble fiber can be cooked until very soft and blended or pureed to improve digestibility. Gut microbes won’t mind if they receive their fiber in softer, bite-sized pieces, and an irritated GI system will appreciate the extra help breaking down the rough textures. Because tolerances to fiber-rich foods vary, it can be helpful to increase fiber consumption slowly for anyone that has been avoiding fiber for some time. The fiber profile of many fruits and vegetables varies widely, so many IBDers find that different fiber sources suit their needs best and help promote the best IBD diet for their needs.

Barbara Olendski, RD, associate professor at the University of Massachusetts, has implemented some of this evidence to create the IBD Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID) which prioritizes foods that feed beneficial bacteria and avoids foods thought to have adverse effects on the gut microbiome such as gluten, corn, and lactose.16 Olendski believes adjustment to the texture of soluble fiber for different disease states is the best way to fuel the gut microbiota and avoid further GI upset until the inflammation subsides. For some of her patients, Olendski suggests the addition of digestive enzymes to aid in the digestion of fiber. Ultimately, because IBD-AID targets each of the three primary mechanisms of IBD via consumption of healthy fibers, it has been shown in practice to help many people achieve remission.

This doesn’t, however, mean the IBD-AID is the only good IBD diet. Here at IBDCoach, we don’t believe there is a single “best” IBD diet. Every case of IBD is unique and every individual’s gut microbiota is unique as well– even identical twins only share about 50% of their gut microbiomes.17 Fiber is an essential component for any IBD diet, but each individual needs to assess their unique situation and needs and adapt their plan accordingly to develop their personalized best diet for inflammatory bowel disease.

Read Our Comprehensive Review of IBD Treatment Strategies

Takeaways

Years of research have demonstrated that certain fiber varieties can fortify the gut’s intestinal barrier, bolster immune function, and fuel optimal microbiome composition. Although there is not enough conclusive evidence to create an official fiber recommendation for people with IBD, the potential of utilizing fiber as an anti-inflammatory therapeutic is quite promising. Of course, some of these beneficial effects may also result from the other nutrients and minerals required for health that are often found in fiber-rich fruits and vegetables. Due to variables like genetics, our unique microbiome, and the incredible heterogeneity of IBD symptoms, there is not a single “best IBD diet.” As always, be sure to speak with your medical team before making any dietary changes, especially for individuals with strictures and intestinal obstruction.

Looking for support on your journey to develop your best IBD diet to achieve remission from IBD? IBDCoach has developed the Adaptive Dietary Framework to help IBDers assess their unique situation and develop their ultimate IBD diet and protocol alongside their health and medical team. Attend our Microcourse: The Foundations of Remission or Schedule an Admissions Call to learn how to get started today.

- Armstrong H, Mander I, Zhang Z, Armstrong D, Wine E. Not All Fibers Are Born Equal; Variable Response to Dietary Fiber Subtypes in IBD. Front Pediatr. 2021;8. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.620189

- Gropper SS, Smith JL, Carr TP. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. Eighth edition. Cengage Learning; 2022.

- Cronin P, Joyce SA, O’Toole PW, O’Connor EM. Dietary Fibre Modulates the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1655. doi:10.3390/nu13051655

- Martinez KB, Leone V, Chang EB. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: Are they linked? Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):130-142. doi:10.1080/19490976.2016.1270811

- Chiba M, Nakane K, Komatsu M. Westernized Diet is the Most Ubiquitous Environmental Factor in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Perm J. 2019;23:18-107. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-107

- Rossi M, Corradini C, Amaretti A, et al. Fermentation of Fructooligosaccharides and Inulin by Bifidobacteria: a Comparative Study of Pure and Fecal Cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(10):6150-6158. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.10.6150-6158.2005

- Parada Venegas D, De la Fuente MK, Landskron G, et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277

- Cavaglieri CR, Nishiyama A, Fernandes LC, Curi R, Miles EA, Calder PC. Differential effects of short-chain fatty acids on proliferation and production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by cultured lymphocytes. Life Sci. 2003;73(13):1683-1690. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00490-9

- Asarat M, Apostolopoulos V, Vasiljevic T, Donkor O. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate Cytokines and Th17/Treg Cells in Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in vitro. Immunol Invest. 2016;45(3):205-222. doi:10.3109/08820139.2015.1122613

- Holscher HD. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2017;8(2):172-184. doi:10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756

- Riva A, Kuzyk O, Forsberg E, et al. A fiber-deprived diet disturbs the fine-scale spatial architecture of the murine colon microbiome. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4366. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12413-0

- Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL. Starving our microbial self: the deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):779-786. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.003

- Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Bäckhed F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(6):705-715. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

- Levine A, Rhodes JM, Lindsay JO, et al. Dietary Guidance From the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2020;18(6):1381-1392. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.01.046

- Pituch-Zdanowska A, Banaszkiewicz A, Albrecht P. The role of dietary fibre in inflammatory bowel disease. Przegla̜d Gastroenterol. 2015;10(3):135-141. doi:10.5114/pg.2015.52753

- IBD Anti-Inflammatory Diet. UMass Chan Medical School. Published March 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.umassmed.edu/nutrition/ibd/ibdaid/

- Turnbaugh PJ, Quince C, Faith JJ, et al. Organismal, genetic, and transcriptional variation in the deeply sequenced gut microbiomes of identical twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(16):7503-7508. doi:10.1073/pnas.1002355107