What is the cure for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)? While there is no permanent cure for Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis, or indeterminate colitis, there are many treatments for IBD that can lead to robust states of remission. Remission is a period where the symptoms of IBD have subsided and the GI tract has healed. A well-rounded, remission-supporting treatment plan for IBD may include IBD medications, IBD diets, supplements, lifestyle changes, mindset, surgical interventions and more. While many people may feel that IBD treatment strategies fall into two main buckets: medical treatments for IBD and natural treatments for IBD, for most IBDers, the perfect treatment strategy for IBD is somewhere in the middle. Whether you are new to IBD or have been around the block a few times, this article is the perfect read to learn more about all of the available treatments for IBD from the classic to the cutting edge.

The information below is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical care. Always consult your doctor if you are seeking medical advice, a diagnosis, or treatment for your condition.

What is IBD?

While we take a deep dive into understanding IBD and its causes in Part 1 of this series, let’s review the basics needed to understand the different treatment options available for this condition.

The inflammatory bowel diseases are idiopathic and chronic immune-mediated conditions including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), and microscopic colitis (MC) that affect all or specific parts of the gastrointestinal tract.1–3 “Idiopathic” essentially means that IBD is somewhat spontaneous—there is no single trigger or underlying cause that results in the development of IBD. IBD is also considered a chronic condition—while many treatments help address the symptoms of IBD, there is currently no true cure for inflammatory bowel disease. Understanding the factors that contribute to the cause of IBD and the biology behind this mysterious condition can help us gain a deeper understanding of how and why different treatment interventions work (or fail). This deeper understanding can help empower IBDers to take charge of their healthcare, advocate for treatments best suited to their unique case, and avoid falling prey to misinformation and promises of cure-alls.

IBD Biology

The intestinal lining is made up of several layers of tissue known as the mucosa that may be affected differently depending on the specific subtype of IBD.

- In Crohn’s disease, any or all layers of the mucosa may be affected by inflammation. Inflammation can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus which can influence which medications are best suited to target the inflammation.

- In ulcerative colitis, only the most superficial layer of the intestinal lining is affected. Inflammation may affect part or all of the colon (pancolitis).

- In microscopic colitis, the inflammation presents as a microscopic build-up of lymphocytes (immune cells) or collagen below the surface of the lining in lymphocytic colitis and collagenous colitis, respectively.

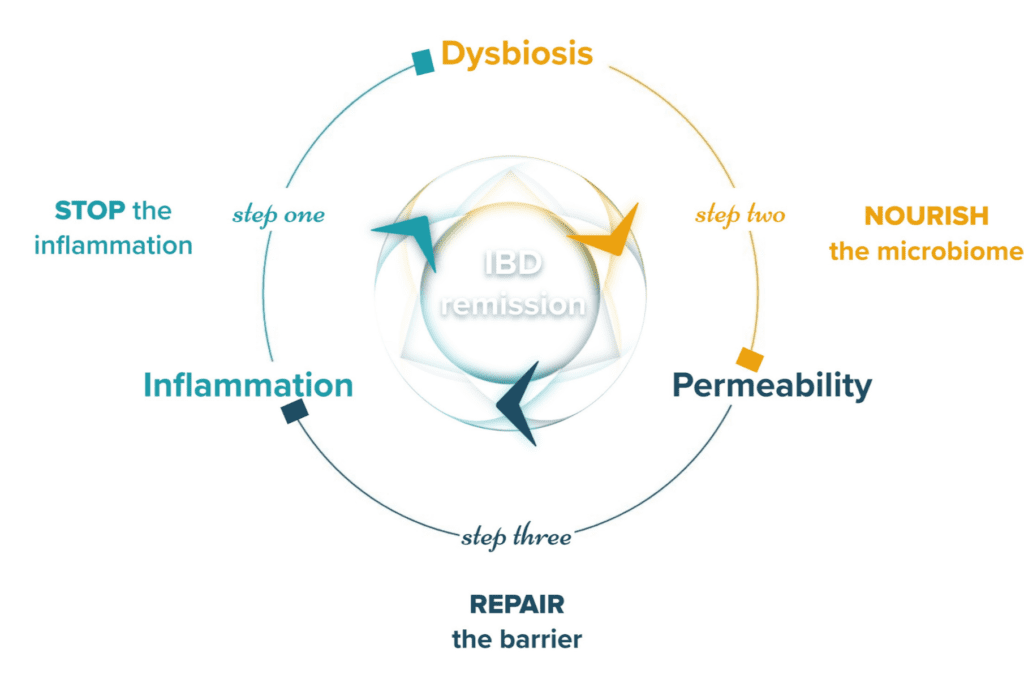

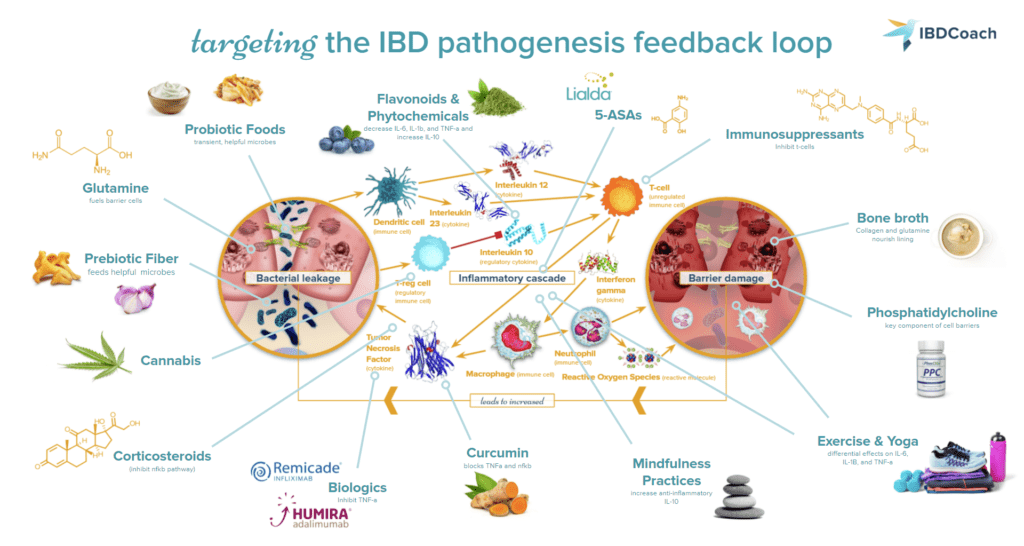

A dysregulated immune response in the lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract results in inflammation of the tissue and subsequent symptoms of IBD.4,5 In the runaway cycle of IBD, increasing intestinal permeability allows things like bacterial particulates to leak across the intestinal lining, triggering an immune response against the invading particulates.6,7 This immune response leads to inflammation and tissue damage. Dysbiosis of the microbiome, or an imbalance of the microbes that inhabit the GI tract, can further contribute to rising inflammation and disruption of the intestinal lining. As inflammation increases and the lining becomes more damaged, more harmful particulates can leak across the barrier and continue this cycle. The most effective IBD protocols must attack all three parts of the IBD cycle:

- Inflammation

- Dysbiosis

- Permeability

These three mechanisms that drive IBD symptoms and pathology help highlight the potential underlying causes of IBD and inspire treatment approaches.

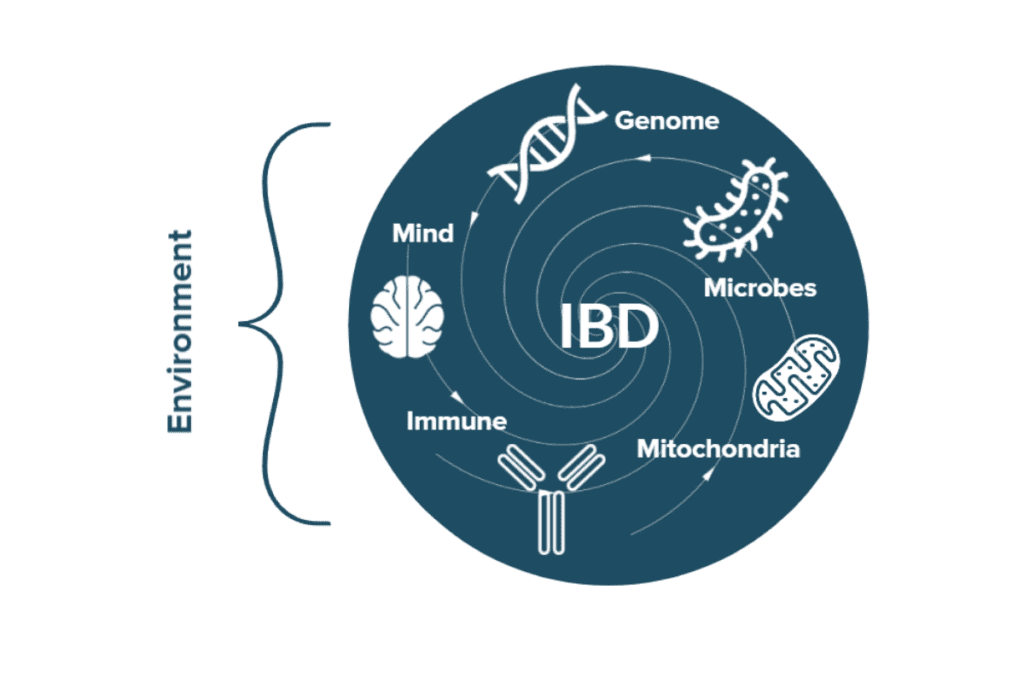

The Cause of IBD

Both genetic and environmental factors appear to contribute to the onset of IBD.8–11 Therefore, both therapeutic and lifestyle interventions are often needed for the successful long-term management of this condition.12–14 Unsurprisingly, many of the genes that have been implicated in increasing the risk and severity of IBD are involved in the regulation of the immune system or the maintenance of the intestinal lining. Still, no single mutation has been found that causes IBD every single time. Even in identical twins, one twin can develop IBD while the other does not.9,15,16 This indicates that the environment also plays a major role in the development and progression of IBD. On top of biological risk factors, environmental factors like dietary patterns, disruptions to the gut microbiome, stress, and lifestyle choices like smoking or the use of hormonal birth control pills have all been associated with IBD risk and pathogenesis.11,17–21 Understanding your unique constellation of risk factors can help individuals better advocate for a personalized treatment plan that works for their needs as they navigate healthcare for IBD.

Read More About the Biology Behind IBD and Its Cause

Frontline Treatments for IBD

Before taking a closer look at the current treatments for IBD, it is essential to remember that there is currently no cure for IBD. In medical terms, a “cure” is a permanent resolution for a particular ailment. While many people with IBD may feel that they have been “cured” when they achieve a robust state of remission and wish to share this joy, there is always a chance that symptoms will return or “flare” in the future. Still, developing a well-rounded and personalized treatment plan for IBD can help promote and maintain deep states of remission.

Our idea of frontline treatments for IBD is continually evolving with breakthroughs in our understanding of the mechanisms that fuel disease activity and promote healing. Classically, medications, surgical interventions, and other medical therapies are considered the “frontline” treatment interventions for IBD. The world of IBD care, however, is coming to understand that dietary strategies, lifestyle interventions, and more all play a central role in IBD treatment strategies.12,22,23 There is no one-size-fits-all treatment for IBD. No two IBD cases are alike, and neither do two “perfect” IBD treatment protocols. Let’s take a closer look at which frontline treatments may be a part of a well-rounded IBD protocol.

Medications for IBD

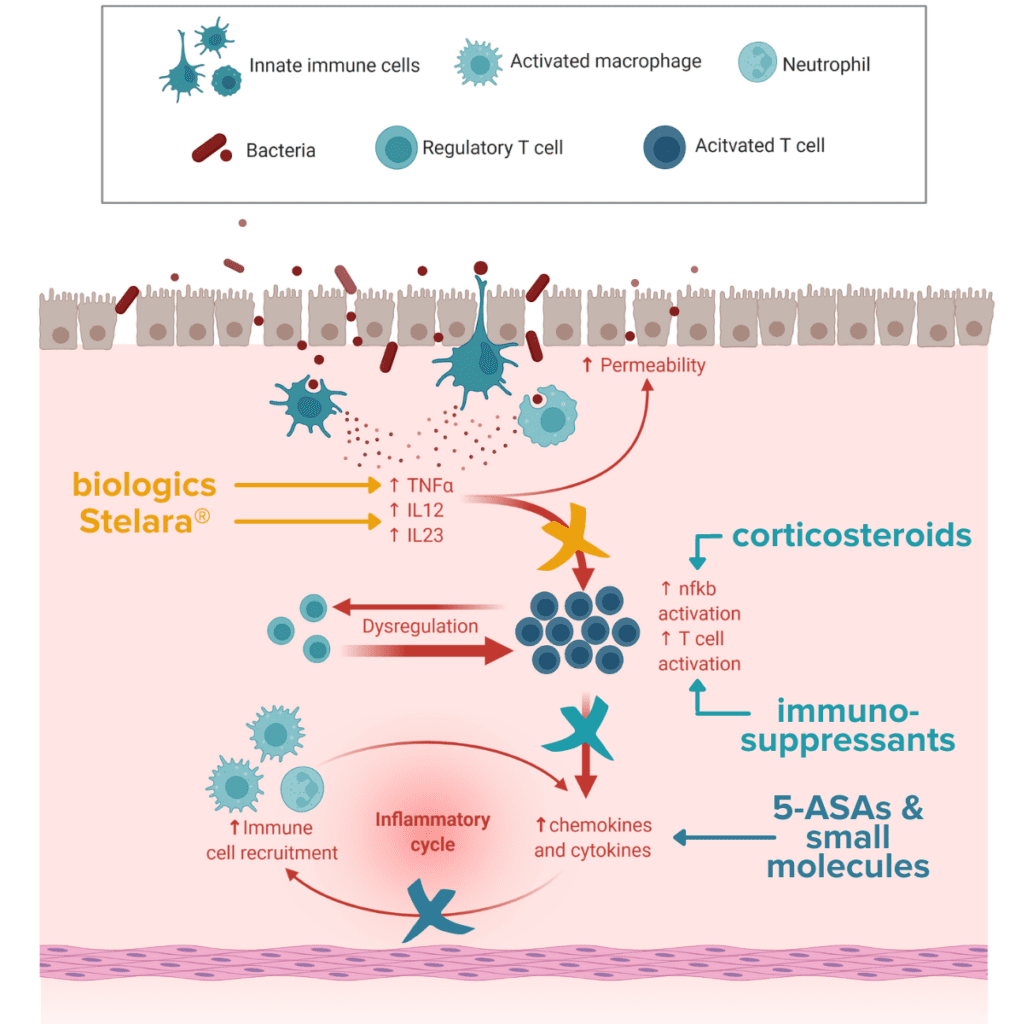

More often than not, IBDs like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis will require the use of medication as a part of treatment during a flare and often during maintenance. IBD medications are powerful and life-saving tools that, when used in harmony with other evidence-based approaches such as diet and lifestyle interventions, can prove vital for a successful recovery. The primary goal of these therapeutics is to achieve remission by targeting overt inflammation in both the short- and long-term.

Short-term medications

- Corticosteroids: Steroids, including prednisone and budesonide, are prescribed during highly active and severe disease phases, typically referred to as flare-ups. Corticosteroids are typically highly effective at controlling inflammation but may vary in their strength and location of delivery depending on the specific formulation.24 Corticosteroids are one of the first-line medications used for microscopic colitis.25,26

Long-Term Medications

- Anti-inflammatories (5-ASAs): Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) are anti-inflammatory medications used for mild to moderate IBD symptoms to induce remission during a flare and to maintain remission. 5-ASAs are considered one of the safest drug therapies for IBD because they have a more limited side effect profile.27,28

- Immunosuppressants: Immunosuppressant medications aim to dampen the overactive immune response to prevent flares and sustain remission in IBD. Immunosuppressants are long- and slow-acting and have side effects including increased risk of infections and some forms of cancer because immunosuppressants act on the entire immune system, not just on the parts impacting IBD. Due to these side effects, immunosuppressants are generally not considered first-choice medications.29

- Biological therapies: Biological therapies such as Remicade® (infliximab) and Humira® (adalimumab) bind to specific proteins involved in the inflammatory response called cytokines, such as TNF-α, to dampen the immune response and quickly lower inflammation. These medications are quickly becoming the gold standard of treatment for moderate to severe CD and UC. Biologics increase the risk of infections and some forms of cancer, such as lymphoma.30–33

- Non-biologic therapies (small molecules): Non-biologic small molecule therapies aim to quickly dampen the immune response by blocking cytokines, important elements of the body’s immune response pathway. Small molecule therapies can increase the risk of infections and some cancers.34–36

Support Medications

- Pain relievers: Many doctors may prescribe pain medications in combination with anti-inflammatories to help manage the symptoms of IBD. 37

- Antibiotics: In some cases, doctors may prescribe antibiotics including ciprofloxacin (Cipro®), metronidazole (Flagyl®), and Rifaximin (Xifaxan®). While antibiotics can carry serious side effects, some antibiotics may be necessary to treat infections that are commonly found in individuals with IBD.38

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin®): For individuals who are also suffering from depression, bupropion is a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI) antidepressant that works in the brain to improve mood. Preliminary data suggests antidepressants can improve disease course in IBD. Bupropion has been shown to improve psychological symptoms and may also reduce inflammation due to interactions on the gut-brain axis. IBDers who have also been diagnosed with depression (which is almost one in three individuals with IBD) may wish to discuss bupropion with their medical team as an option.39,40

IBD Medication Stigma

When used with intention as part of a well-rounded IBD protocol, medications are a powerful tool to safely promote and maintain remission. Unfortunately, the use of medication is often highly stigmatized and viewed in a negative light. It is common to feel apprehensive about side effects and fear that certain medications may become lifelong crutches to keep flares at bay. IBD medications are NOT life sentences. Appropriate utilization of medications can lower inflammation and allow the GI tract the space it needs to heal and recover. It is important to remember that having uncontrolled, active IBD and inflammation for long periods also carries major risks. Evidence suggests that long-term uncontrolled IBD may also increase the risk of some forms of cancer, hospitalization, and need for surgery. Getting inflammation and flares under control is one of the best things people with IBD can do to promote their long-term health and wellbeing.

Whether or not medications are a part of your journey to remission is a choice to be made between you and your healthcare team. No IBDer should ever be shamed for their choice for or against medication use. Most importantly, IBDers should be encouraged to advocate for their unique needs and make evidence-based decisions with their healthcare team about which treatments are best for them and best to support achieving and maintaining remission.

Surgical Interventions for IBD

In more than half of CD cases and many UC cases, surgical intervention is required to remove extensively damaged tissue from the GI tract.41–43 Some of the most common surgical interventions used in IBD can include colectomy (removal of the colon) and resection (removal of a small segment of the small intestine or colon). Surgical interventions may also be used to help correct complications of IBD such as fistulae or strictures. One goal of most treatment strategies is to control inflammation and achieve remission before surgical intervention is required. IBDers should not, however, feel that they have failed if they require surgical intervention. The risks of avoiding surgery despite extensive tissue damage and uncontrolled inflammation can often far outweigh the benefits. It is essential to find a surgeon that understands your unique situation and is willing to work closely with your other doctors to develop a plan that is best for you.

Cutting Edge and Investigative Treatments for IBD

Recent advances in the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease have given rise to several cutting-edge and investigative medical treatment options. While these options are not yet formally approved for IBD, there are ongoing and promising clinical trials that suggest these options may someday soon be a regular component of IBD treatment protocols. Some individuals with IBD may wish to participate in clinical trials for emerging therapies as a part of their IBD protocol.

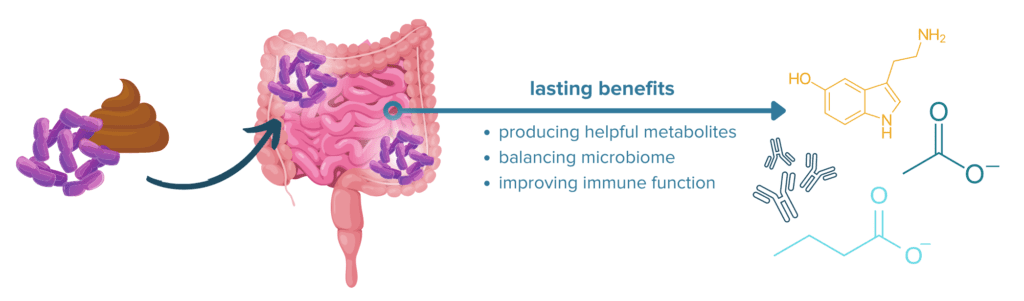

Fecal Microbial Transplants for IBD

Recent evidence suggests that fecal microbial transplant (FMT) is an encouraging future therapy for IBD. New populations of microbes are transplanted into the GI tract to restore the balance between helpful and harmful gut inhabitants. Remission rates have ranged from 10% to 80% in different studies on FMT. In general, it appears that FMT is primarily effective in cases of UC and some cases of CD with high colonic involvement. Ongoing studies aim to refine the technique and identify characteristics that lead to successful outcomes in patients receiving FMT.44–46

Learn More About FMT, the Microbiome & IBD Remission

Cannabis for IBD

Cannabis contains two primary active compounds: THC and CBD. CBD possesses known anti-inflammatory properties and may promote relief from some IBD symptoms. Additionally, many people with IBD report that cannabis helps alleviate chronic pain and/or psychological effects of IBD.47–49 Cannabis may not be legal for recreational use, medical use, or either in some countries, states, and municipalities. Never use cannabis without the approval of your physician.

Read more about Cannabis and IBD

The “Natural” Treatments for IBD

While dietary strategies, supplements, lifestyle changes, mindset shifts, and mental healthcare are not often considered as frontline treatments for IBD, a growing body of scientific research and clinical evidence suggests these approaches are all pivotal in supporting positive outcomes for people with CD, UC, and MC. For some cases of IBD, individuals may wish to pursue some of these more natural treatment options for IBD before trying medications. This may work for some individuals, but may not be feasible for others. As noted above, it is essential to work closely with your healthcare team to develop the IBD protocol that best suits your needs and unique case of IBD.

Diet and Nutritional Interventions for IBD

Dietary changes are perhaps one of the most foundational interventions for inflammatory bowel disease. Historically, many physicians believed that diet didn’t matter in IBD. This belief is often fueled by the fact that many medications can be powerful enough at controlling symptoms of IBD that dietary triggers are not immediately obvious. A growing wealth of evidence now suggests that some dietary patterns (like those low in fiber but high in added sugars and saturated fats) can dramatically increase the risk and severity of IBD.11,50 Other dietary patterns (such as those high in fiber and flavonoids but low in added sugars and processed foods) can be beneficial for symptoms of IBD and for promoting remission.51–53

Learn About Fiber and IBD

Unfortunately, the perfect IBD diet does not exist. Every case of IBD is different because each individual is affected by their unique constellation of risk factors and differences in their ongoing disease activity and treatment protocol. Because of this, the “perfect IBD diet” for one person is most likely not the “perfect IBD diet” for the next. Several foundational dietary strategies have evolved as good starting points for individuals seeking to leverage the power of nutrition to support their journey to remission. These strategies are:

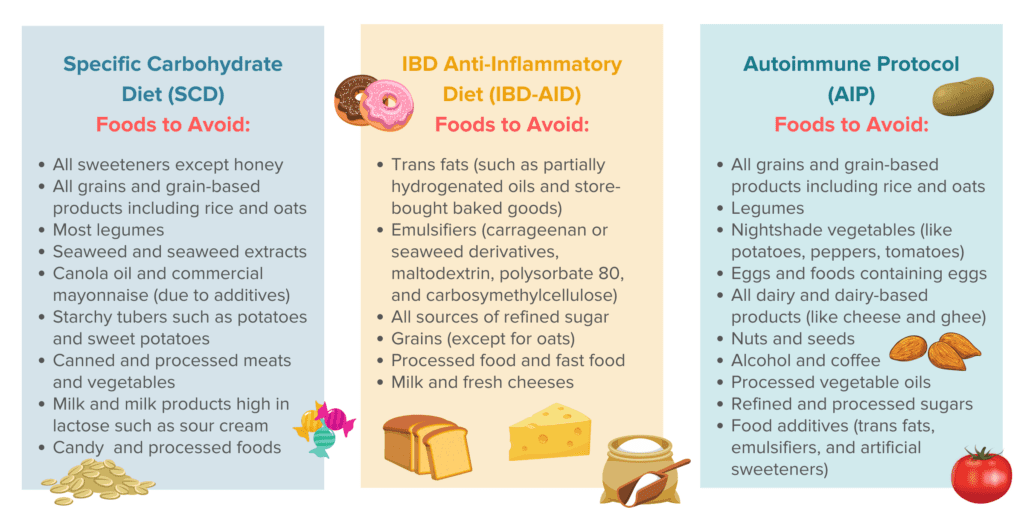

- The Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD): Perhaps one of the most restrictive diets used to help manage symptoms of IBD, the SCD was developed on the idea that certain forms of carbohydrates are more difficult to digest than others, leaving behind fuel for harmful gut microbes, potentially exacerbating symptoms of IBD and immune activity. While evidence on the mechanism behind the SCD has been mixed, this dietary strategy is one of the most thoroughly studied IBD diets and is a solid foundation for many individuals with IBD around which to build their personalized dietary strategy.54–56

- The IBD Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID): The IBD-AID is a more recent and somewhat less restrictive evolution that shares many foundations with the SCD. Like the SCD, the IBD-AID promotes removing certain foods that are thought to promote inflammation and dysbiosis (imbalance in the gut microbiome).13,57

- The Autoimmune Protocol (AIP): While not specifically developed for IBD, the AIP is a dietary strategy that was developed to improve symptoms of autoimmune conditions by removing foods that are known to support inflammation or heightened immune reactivity. Some IBDers find this dietary strategy helps improve their IBD symptoms, while others find this strategy to be too permissive of certain food triggers.58,59

Other dietary strategies commonly used by individuals with IBD include the Mediterranean diet,60–62 vegan and plant-based diets,63,64 and carnivore diets. Oftentimes, supporters of one particular dietary strategy may tout it as a cure-all or guaranteed fix for people with IBD. Remember, there is no curative diet in IBD. While dietary strategies may alleviate symptoms and support remission, IBD is a lifetime condition that may always “flare” in the future. Additionally, what works for one person is not guaranteed to work for another because all IBDers have their own unique risks and circumstances. We can appreciate and learn from the experience of others while not forcing all IBDers into a mold. Many of these diets have some level of evidence that suggests they either promote short-term symptom relief or help lay the groundwork for lasting remission65—especially when adapted to your unique needs and used as a part of a well-rounded IBD protocol.

Supplements and Herbs for IBD

Supplements and herbs are a non-foundational addition to a well-planned, holistic IBD protocol. Many vitamins, amino acids, and herbal supplements have shown promising abilities to reduce inflammation in the GI tract and promote helpful microbes in the gut.52,66–70 By helping reduce inflammation and promoting helpful inhabitants in your intestinal flora and fauna, supplements can aid in giving the intestinal barrier the environment it needs to heal and rebuild. In many cases, supplements can be a great way to “fine-tune” an IBD protocol and tailor it to an individual’s unique needs. Many supplements and herbs have less scientific evidence when compared to frontline medications of IBD and may be contraindicated with certain medications for IBD or certain symptoms of IBD. It is important to consult with your healthcare professionals before adding supplements to your IBD protocol to assess the potential risks and benefits.

Lifestyle Changes for IBD

Lifestyle changes to support remission from IBD can encompass many different strategies including meditation and mindfulness, mindset shifts, exercise, and stress relief. While many of these strategies alone may not be adequate to induce and maintain remission, when used as a part of a well-rounded IBD protocol, lifestyle changes can help bolster your efforts to reduce stress, lower inflammation, and maintain a positive mindset toward your treatment and goals. Some of the many evidence-based lifestyle factors known to influence symptoms of IBD and IBD treatment outcomes are:

- Mindfulness Practices: Mindfulness practices like journaling, yoga, meditation, and visualization are a beneficial part of many IBD protocols because they can help improve the mind-body connection, lower stress and inflammation, promote mental and emotional wellbeing, and support feeling grounded in the present moment.71,72

- Mindset Practices: Mindset practices are a key component of achieving and maintaining remission for many people with IBD. The road to remission is full of ups and downs—in a flare, it feels like mostly downs. Practicing a positive mindset can help put setbacks in perspective and keep goals focused on the future and focused on achieving remission. Celebrate successes no matter how small, honor your needs and feelings, and find ways to move forward from setbacks. 73

- Exercise: Exercise can both support or detract from a well-rounded IBD protocol. Strenuous exercise can increase systemic inflammation and may be detrimental during a flare. Gentle exercise can reduce inflammation and promote mindfulness and stress relief. Finding the right balance of exercise can help ensure that your physical and emotional needs are met.74–76

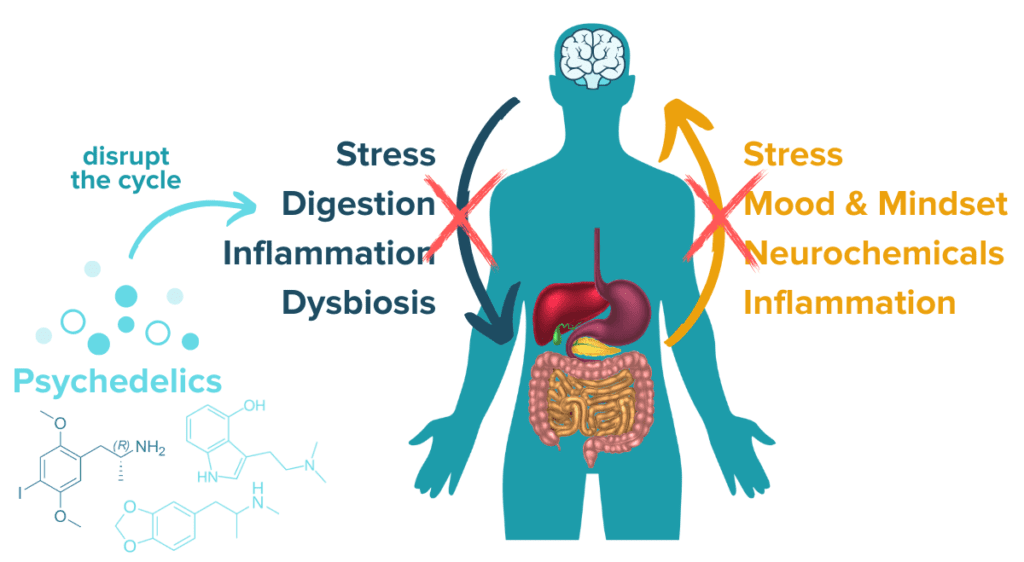

- Stress management: Stress management, which can include almost all of the above lifestyle factors, plays a major role in achieving and maintaining remission for most IBDers. Stress, largely through the microbiome-gut-brain axis, plays a major role in gut health and the immune response. Uncontrolled stress can have serious consequences for symptoms of IBD.19,77–81

Read More About Stress and the Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis

- Other lifestyle choices: Other lifestyle choices, such as smoking, drinking, or taking hormonal birth control pills, may be having surprising impacts on your symptoms of IBD and treatment outcomes.20,21 When feeling stuck on the road to remission, it can be worth turning over new rocks and investigating what other factors may be contributing to your IBD.

The Surprising Link Between Oral Contraceptives and IBD

Meditation and visualization have proven benefits for stress and inflammation reduction. Indeed, excess stress fuels the activation of inflammatory cascades and can exacerbate many IBD symptoms. Stress has also been proven to adversely affect the gut microbiome composition in humans and has been indicated as a potential factor that drives increased intestinal permeability. Adopting a growth mindset, setting goals, and envisioning your future have all been linked to promoting success and reducing stress. Taking a step back, doing something you find relaxing, and rewiring your mindset for growth and positivity have real, physiological benefits that will help you achieve remission.

Psychedelic Therapies for IBD

One very interesting emerging therapy for many chronic health conditions is the use of psychedelic substances in a therapeutic setting. A growing body of evidence suggests that certain psychedelic compounds like ketamine, psilocybin mushrooms, or MDMA may have benefits for various immune- and stress-related conditions when administered by a qualified healthcare professional.82–85 Early scientific evidence suggests that some of these benefits may extend to inflammatory bowel diseases.

Could Psychedelics be the Next Natural Treatment for IBD?

Mental Healthcare for IBD

Mental healthcare is one of the least discussed treatment interventions for IBD, but it is perhaps one of the most important. Almost one-third of individuals with IBD also suffer from depression or anxiety, and many more still also have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from their diagnosis or medical emergencies.86–89 If that wasn’t enough, some evidence suggests that a majority of people with IBD suffer from disordered eating patterns and food fears that negatively impact their quality of life.90–93 IBD and coping with a chronic condition affect mental health. It is okay not to be okay. It is okay to seek help for your mental health if you are struggling. You are not alone in that struggle and you deserve to feel better. Many therapists specialize in individuals with chronic health conditions and can be a great fit for IBD. Supporting your mental health is one of the best ways to make space for your physical well-being.

Special Considerations for IBD Treatments

We have said it before and we will say it here again: every single case of IBD, whether it is Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, indeterminate colitis, or microscopic colitis, is unique. While many of the strategies discussed above have a place in a well-rounded and individualized IBD treatment plan, there are some additional considerations for special cases of IBD that are worth considering.

Treatment Considerations for Refractory IBD

Refractory IBD is CD or UC that is unresponsive to conventional medication therapies. Combining drug therapies, changing medications, and incorporating other treatment strategies such as FMT are all ways that doctors may attempt to treat refractory IBD.94–97 In many cases of refractory IBD, surgical intervention is required as a last resort. Especially in CD, disease activity can return in the remaining portion of the intestine so many sources advise using surgery only when it is strictly needed.

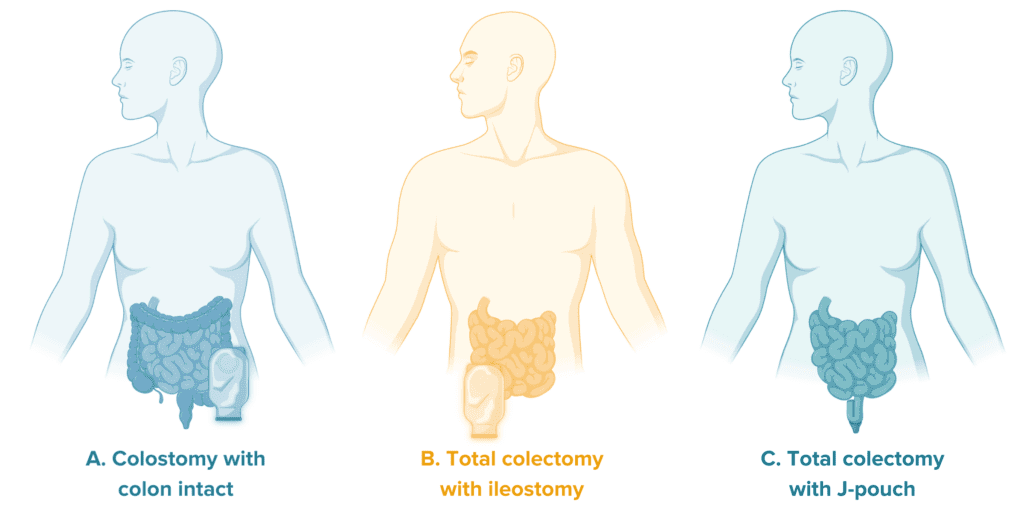

Treatment Considerations for Ostomies & J-Pouches

Some surgical interventions for IBD may be an ileostomy or a colostomy.42,43,98 Ostomy surgery is when waste is diverted from the digestive tract into an external pouch (known as an ostomy bag) instead of through the remainder of the GI tract. Ostomies may be temporary or permanent depending on the case. In temporary cases, the flow of waste may be diverted to an ostomy bag to allow time for the intestines to heal before eventually removing the ostomy bag and reconnecting the intestine or colon. Other times, such as in a total proctocolectomy, the ostomy may be permanent. As an alternative to an ostomy, many patients with UC may be able to have a j-pouch surgery when a total colectomy is required. In this surgery, an ileal pouch anal-anastomosis or j-pouch is constructed from a portion of the small intestine and connected to the rectum to function in place of the removed colon. In either case, medications, changes to dietary strategies, and lifestyle adjustments may still be needed to best support the success of this treatment intervention.

As an important note, ostomies can often carry a stigma in the IBD community and may feel like a last resort or failure. Ostomies are not failures. Ostomies are a life-saving treatment intervention that can get individuals suffering from severe IBD back to a state of wellbeing and enjoying more freedom and comfort in life.

Treatment Considerations for Children with IBD

Diagnosis of IBD among children is rising around the world. In many cases, IBD can be more serious in children. Additionally, longer periods of uncontrolled, highly active inflammation may be associated with worse treatment outcomes in the long run.99,100 This means that getting IBD well under control in those diagnosed at a younger age is of critical importance to set them up for success and sustained wellbeing. Many of the treatment approaches discussed above may still be used in children, including medications, dietary changes, and lifestyle interventions. One additional option commonly used in children with IBD, especially CD, is exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN).101,102 EEN, a kind of formula feeding, can be successful at inducing remission and providing adequate nutrition to children so they can continue to grow and thrive.

It is essential to help children understand their condition and achieve independence in managing their treatment protocol as they grow to support good treatment outcomes in adulthood.103 IBDCoach’s Youth Program is tailored to provide support resources and personalized attention for both children with IBD and their parents and loved ones. Having a child with IBD can be extremely difficult for parents and loved ones, and they may often find that they need support and resources to help with the stress they are enduring. IBDCoach is here for you.

Very Early Onset IBD (VEO-IBD)

Very early-onset IBD is a kind of IBD that is diagnosed in children below the age of six. Genetic risk factors and immune deficiencies are found to play an increasingly central role in the development of VEO-IBD. Because of this, the progression of VEO-IBD can be more aggressive and less responsive to standard treatment interventions.104,105 Finding doctors that specialize in VEO-IBD and have access to the most cutting-edge treatment options may be an important element of IBD care for children with VEO-IBD.

Treatment Considerations for IBD Caregivers

Inflammatory bowel disease affects more than just the IBDer: it is incredibly difficult for loved ones to witness someone they care about struggling with such a debilitating, lifetime condition. This is another seldom discussed element of IBD-related care. IBD can take a toll on the parents, children, partners, and friends of the individual suffering from IBD. In many cases, loved ones of IBDers often struggle to know how to support the IBDer in their life or feel helpless in their role as a caregiver for their loved one. Loving and caring for someone with a chronic condition like IBD is not easy. As a caretaker, taking advantage of support resources for your own physical and mental wellbeing can also go a long way to support the IBDer in your life. At IBDCoach, we believe that IBD is a family affair, and we have a robust support network for the loved ones of our community members.

Overcoming Contradictory Advice on IBD Treatments

What is the BEST treatment for IBD? Is it natural treatments for IBD? Holistic treatments for IBD? Medications for IBD? Diets for IBD? There is no perfect answer.

One reality that most people with IBD face when navigating their healthcare is being confronted with conflicting advice and contradictory sources of information. Much of this is because our understanding of IBD treatments is evolving every single day. Researchers and healthcare providers are constantly expanding their knowledge of which medications are most effective when, how to incorporate dietary and lifestyle strategies that work best for different individuals, and more.

While we have tried to touch on as many IBD-treatment strategies as possible in this article, there are many more options that have been investigated and are being discovered every single day. Staying up-to-date with the latest developments on IBD treatments is essential to getting the best possible advice for IBD treatments. Additionally, avoiding one-sided sources of information and sources that are strictly “anti-medication” or “anti-natural approach” can help ensure information is unbiased and more accurate. While each IBDer is entitled to develop their own treatment goals and have their own opinions about which strategies they are interested in pursuing, it is important to understand there is evidence to support both medical treatment options for IBD and natural or holistic treatments for IBD. There is no one-size-fits-all treatment for IBD and any source claiming the contrary is misguiding their followers.

One essential trick to help navigate contradictory advice on IBD treatments is to build a well-rounded and diverse healthcare team that understands your unique case, needs, and treatment goals. Many healthcare practitioners specialize in natural treatments for IBD, dietary strategies for IBD, and frontline treatments for IBD. Having a team that is equipped to tackle IBD from all angles and understands the unique goals of each individual IBDer can dramatically change the trajectory of treatment outcomes.

Looking Forward: Life with IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease has no cure, but it does have many evidence-based treatment approaches that combine to make well-rounded, personalized, and effective treatment protocols. While every individual is entitled to their preferences regarding which strategies they and their doctor feel are right for them, we are all bound by our shared mission to achieve robust and lasting remission.

At the end of the day, most IBDers just want to live a normal life and find a way to thrive despite their condition. With a well-rounded treatment plan, this is possible for every IBDer out there. Life with IBD is full of ups and downs, unexpected hardships and surprising joys. Join us for the final installment of this three-part series to dive into Life with IBD.

Ready to get started on building your individualized Remission Master Plan? Sign up for a complimentary admissions call today for an in-depth review of your case. We’ll discuss your unique needs and goals and figure out how to get you started on the road to remission.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – Diagnosis and treatment – Mayo Clinic. Accessed February 15, 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353320

- Microscopic colitis – Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. Accessed March 21, 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/microscopic-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351478

- CDC -What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)? – Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Division of Population Health. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed November 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/what-is-IBD.htm

- de Mattos BRR, Garcia MPG, Nogueira JB, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview of Immune Mechanisms and Biological Treatments. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:493012. doi:10.1155/2015/493012

- Ramos GP, Papadakis KA. Mechanisms of Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):155-165. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.013

- Chang J, Leong RW, Wasinger VC, Ip M, Yang M, Phan TG. Impaired Intestinal Permeability Contributes to Ongoing Bowel Symptoms in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Mucosal Healing. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(3):723-731.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.056

- Ahmad R, Sorrell MF, Batra SK, Dhawan P, Singh AB. Gut permeability and mucosal inflammation: bad, good or context dependent. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(2):307-317. doi:10.1038/mi.2016.128

- Loddo I, Romano C. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Genetics, Epigenetics, and Pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2015;6. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00551

- Cleynen I, Boucher G, Jostins L, et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study. The Lancet. 2016;387(10014):156-167. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00465-1

- Carreras-Torres R, Ibáñez-Sanz G, Obón-Santacana M, Duell EJ, Moreno V. Identifying environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19273. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76361-2

- Chiba M, Nakane K, Komatsu M. Westernized Diet is the Most Ubiquitous Environmental Factor in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Perm J. 2019;23:18-107. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-107

- Cai Z, Wang S, Li J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front Med. 2021;8. Accessed March 21, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmed.2021.765474

- Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014;13(1):5. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-13-5

- Verstockt B, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G. New treatment options for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(5):585-590. doi:10.1007/s00535-018-1449-z

- Gordon H, Trier Moller F, Andersen V, Harbord M. Heritability in inflammatory bowel disease: from the first twin study to genome-wide association studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(6):1428-1434. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000393

- Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Hughes AO, Thompson JR, Wicks AC, Mayberry JF. Prevalence and family risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: an epidemiological study among Europeans and south Asians in Leicestershire. Gut. 1993;34(11):1547-1551. doi:10.1136/gut.34.11.1547

- Glassner KL, Abraham BP, Quigley EMM. The microbiome and inflammatory bowel disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):16-27. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.003

- Halfvarson J, Brislawn CJ, Lamendella R, et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2(5):1-7. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.4

- Gao X, Cao Q, Cheng Y, et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(13):E2960-E2969. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720696115

- Rosenfeld G, Bressler B. The truth about cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1407-1408. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.190

- Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62(8):1153-1159. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302362

- Complementary Medicine. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/ibd/complementary-medicine

- Green N, Miller T, Suskind D, Lee D. A Review of Dietary Therapy for IBD and a Vision for the Future. Nutrients. 2019;11(5):947. doi:10.3390/nu11050947

- Bruscoli S, Febo M, Riccardi C, Migliorati G. Glucocorticoid Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Clinical Practice. Front Immunol. 2021;12:691480. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.691480

- Boland K, Nguyen GC. Microscopic Colitis: A Review of Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;13(11):671-677.

- Pardi DS. Diagnosis and Management of Microscopic Colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):78-85. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.477

- Nielsen OH, Munck LK. Drug Insight: aminosalicylates for the treatment of IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4(3):160-170. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep0696

- Aminosalicylates. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd/medication/aminosalicylates

- Zenlea T, Peppercorn MA. Immunosuppressive therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2014;20(12):3146-3152. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3146

- Danese S, Vuitton L, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Biologic agents for IBD: practical insights. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(9):537-545. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.135

- Efficacy | STELARA® (ustekinumab) HCP. STELARA® (ustekinumab). Published July 2, 2020. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://www.stelarahcp.com/ulcerative-colitis/efficacy

- Dave M, Papadakis KA, Faubion WA. Immunology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Molecular Targets for Biologics. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(3):405-424. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.003

- Rawla P, Sunkara T, Raj JP. Role of biologics and biosimilars in inflammatory bowel disease: current trends and future perspectives. J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:215-226. doi:10.2147/JIR.S165330

- Baumgart DC, Le Berre C. Newer Biologic and Small-Molecule Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ingelfinger JR, ed. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1302-1315. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1907607

- Ben Ghezala I, Charkaoui M, Michiels C, Bardou M, Luu M. Small Molecule Drugs in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(7):637. doi:10.3390/ph14070637

- Lucaciu LA, Seicean R, Seicean A. Small molecule drugs in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases: which one, when and why? – a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32(6):669-677. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000001730

- Docherty MJ, Jones RCW, Wallace MS. Managing Pain in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;7(9):592-601.

- Nitzan O. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(3):1078. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.1078

- Brustolim D, Ribeiro-dos-Santos R, Kast RE, Altschuler EL, Soares MBP. A new chapter opens in anti-inflammatory treatments: the antidepressant bupropion lowers production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(6):903-907. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2005.12.007

- Kristensen MS, Kjærulff TM, Ersbøll AK, Green A, Hallas J, Thygesen LC. The Influence of Antidepressants on the Disease Course Among Patients With Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis-A Danish Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(5):886-893. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy367

- Sica GS, Biancone L. Surgery for inflammatory bowel disease in the era of laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2013;19(16):2445-2448. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2445

- Surgery for Ulcerative Colitis. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ulcerative-colitis/surgery

- Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-crohns-disease/treatment/surgery

- Allegretti JR, Kelly CR, Grinspan A, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Outcomes Following Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Recurrent C. difficile Infection. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(9):1371-1378. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa283

- Lopez J, Grinspan A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12(6):374-379.

- Tan P, Li X, Shen J, Feng Q. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Update. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2020.574533

- Ahmed W, Katz S. Therapeutic Use of Cannabis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12(11):668-679.

- Leinwand KL, Gerich ME, Hoffenberg EJ, Collins CB. Manipulation of the endocannabinoid system in colitis: A comprehensive review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(2):192-199. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000001004

- Crohn’s and Colitis Canada. Cannabis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease.; 2019. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TIMh2R49HgQ

- Narula N, Wong ECL, Dehghan M, et al. Association of ultra-processed food intake with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. Published online July 14, 2021:n1554. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1554

- Armstrong H, Mander I, Zhang Z, Armstrong D, Wine E. Not All Fibers Are Born Equal; Variable Response to Dietary Fiber Subtypes in IBD. Front Pediatr. 2021;8. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.620189

- Salaritabar A, Darvishi B, Hadjiakhoondi F, et al. Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(28):5097. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5097

- Sasson AN, Ananthakrishnan AN, Raman M. Diet in Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2021;19(3):425-435.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.054

- Obih C, Wahbeh G, Lee D, et al. Specific carbohydrate diet for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice within an academic IBD center. Nutrition. 2016;32(4):418-425. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.08.025

- Kakodkar S, Mutlu EA. Diet as a therapeutic option for adult inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):745-767. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.08.016

- Breaking the Vicious Cycle: Intestinal Health Through Diet | Eating for your Health. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.eatingforyourhealth.org/content/breaking-vicious-cycle-intestinal-health-through-diet

- IBD Anti-Inflammatory Diet. UMass Chan Medical School. Published March 4, 2015. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.umassmed.edu/nutrition/ibd/ibdaid/

- Konijeti GG, Kim N, Lewis JD, et al. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):2054-2060. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000001221

- AIP (Autoimmune Protocol) Diet: Overview, Food List, and Guide. Healthline. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/aip-diet-autoimmune-protocol-diet

- Chicco F, Magrì S, Cingolani A, et al. Multidimensional Impact of Mediterranean Diet on IBD Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(1):1-9. doi:10.1093/ibd/izaa097

- Papada E, Amerikanou C, Forbes A, Kaliora AC. Adherence to Mediterranean diet in Crohn’s disease. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(3):1115-1121. doi:10.1007/s00394-019-01972-z

- Vrdoljak J, Vilović M, Živković PM, et al. Mediterranean Diet Adherence and Dietary Attitudes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3429. doi:10.3390/nu12113429

- Grosse CSJ, Christophersen CT, Devine A, Lawrance IC. The role of a plant-based diet in the pathogenesis, etiology and management of the inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14(3):137-145. doi:10.1080/17474124.2020.1733413

- Chiba M, Ishii H, Komatsu M. Recommendation of plant-based diets for inflammatory bowel disease. Transl Pediatr. 2019;8(1):23-27. doi:10.21037/tp.2018.12.02

- Nutritional Therapy for IBD – Home. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://ntforibd.org/

- González R, Ballester I, López-Posadas R, et al. Effects of Flavonoids and other Polyphenols on Inflammation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2011;51(4):331-362. doi:10.1080/10408390903584094

- Baliga MS, Joseph N, Venkataranganna MV, Saxena A, Ponemone V, Fayad R. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric in the prevention and treatment of ulcerative colitis: preclinical and clinical observations. Food Funct. 2012;3(11):1109-1117. doi:10.1039/c2fo30097d

- Gubatan J, Moss AC. Vitamin D in inflammatory bowel disease: more than just a supplement. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34(4):217-225. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000449

- Di Sabatino A, Cazzola P, Ciccocioppo R, et al. Efficacy of butyrate in the treatment of mild to moderate Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis Suppl. 2007;1(1):31-35. doi:10.1016/S1594-5804(08)60009-1

- Parian A, Limketkai BN. Dietary Supplement Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(2):180-188. doi:10.2174/1381612822666151112145033

- González-Moret R, Cebolla A, Cortés X, et al. The effect of a mindfulness-based therapy on different biomarkers among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6071. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-63168-4

- Ewais T, Begun J, Kenny M, et al. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for youth with inflammatory bowel disease and depression – Findings from a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2021;149:110594. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110594

- Sarrasin JB, Nenciovici L, Foisy LMB, Allaire-Duquette G, Riopel M, Masson S. Effects of teaching the concept of neuroplasticity to induce a growth mindset on motivation, achievement, and brain activity: A meta-analysis. Trends Neurosci Educ. 2018;12:22-31. doi:10.1016/j.tine.2018.07.003

- Bilski J, Brzozowski B, Mazur-Bialy A, Sliwowski Z, Brzozowski T. The Role of Physical Exercise in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:1-14. doi:10.1155/2014/429031

- Keirns BH, Koemel NA, Sciarrillo CM, Anderson KL, Emerson SR. Exercise and intestinal permeability: another form of exercise-induced hormesis? Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;319(4):G512-G518. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00232.2020

- Bilski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Brzozowski B, et al. Can exercise affect the course of inflammatory bowel disease? Experimental and clinical evidence. Pharmacol Rep. 2016;68(4):827-836. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2016.04.009

- Berding A, Witte C, Gottschald M, et al. Beneficial Effects of Education on Emotional Distress, Self-Management, and Coping in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Study. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2017;1(4):182-190. doi:10.1159/000452989

- Dube SR, Fairweather D, Pearson WS, Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Croft JB. Cumulative Childhood Stress and Autoimmune Diseases in Adults. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):243-250. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888

- Jedel S, Hoffman A, Merriman P, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction to Prevent Flare-up in Patients with Inactive Ulcerative Colitis. Digestion. 2014;89(2):142-155. doi:10.1159/000356316

- Sun Y, Li L, Xie R, Wang B, Jiang K, Cao H. Stress Triggers Flare of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adults. Front Pediatr. 2019;7. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00432

- Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54(10):1481-1491. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.064261

- Flanagan TW, Nichols CD. Psychedelics as anti-inflammatory agents. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):363-375. doi:10.1080/09540261.2018.1481827

- Aleksandrova LR, Phillips AG. Neuroplasticity as a convergent mechanism of ketamine and classical psychedelics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42(11):929-942. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2021.08.003

- Thompson C, Szabo A. Psychedelics as a novel approach to treating autoimmune conditions. Immunol Lett. 2020;228:45-54. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2020.10.001

- Saplakoglu Y. FDA Calls Psychedelic Psilocybin a “Breakthrough Therapy” for Severe Depression. livescience.com. Published November 25, 2019. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.livescience.com/psilocybin-depression-breakthrough-therapy.html

- Byrne G, Rosenfeld G, Leung Y, et al. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:e6496727. doi:10.1155/2017/6496727

- Neuendorf R, Harding A, Stello N, Hanes D, Wahbeh H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2016;87:70-80. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.06.001

- Cámara RJA, Gander ML, Begré S, Känel R von, Group SIBDCS. Post-traumatic stress in Crohn’s disease and its association with disease activity. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2011;2(1):2-9. doi:10.1136/fg.2010.002733

- Glynn H, Möller SP, Wilding H, Apputhurai P, Moore G, Knowles SR. Prevalence and Impact of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Gastrointestinal Conditions: A Systematic Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(12):4109-4119. doi:10.1007/s10620-020-06798-y

- Day AS, Yao CK, Costello SP, Andrews JM, Bryant RV. Food‐related quality of life in adults with inflammatory bowel disease is associated with restrictive eating behaviour, disease activity and surgery: A prospective multicentre observational study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35(1):234-244. doi:10.1111/jhn.12920

- Yelencich E, Truong E, Widaman AM, et al. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Prevalent Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;0(0). doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.009

- Kuźnicki P, Neubauer K. Emerging Comorbidities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Eating Disorders, Alcohol and Narcotics Misuse. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19):4623. doi:10.3390/jcm10194623

- Marsh A, Kinneally J, Robertson T, Lord A, Young A, Radford –Smith G. Food avoidance in outpatients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Who, what and why. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2019;31:10-16. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2019.03.018

- Tremaine W. Refractory IBD: medical management. Neth J Med. 1997;50(2):S12-S14. doi:10.1016/S0300-2977(96)00065-4

- Tanida S, Ozeki K, Mizoshita T, et al. Managing refractory Crohn’s disease: challenges and solutions. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:131-140. doi:10.2147/CEG.S61868

- Pineton de Chambrun G, Tassy B, Kollen L, et al. Refractory ulcerative proctitis: How to treat it? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;32-33:49-57. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2018.05.009

- Managing refractory IBD – Mayo Clinic. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/digestive-diseases/news/managing-refractory-ibd/mac-20430383

- Relief IBD. Surgery for IBD. IBDrelief. Accessed March 23, 2022. http://www.ibdrelief.com/learn/treatment/surgery

- Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over 30 Years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(2):375-381.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.016

- Manser CN, Borovicka J, Seibold F, et al. Risk factors for complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2016;4(2):281-287. doi:10.1177/2050640615627533

- Day AS, Lopez RN. Exclusive enteral nutrition in children with Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015;21(22):6809-6816. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i22.6809

- Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1053-1060. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1982

- Kahn SA. The Transition From Pediatric to Adult Inflammatory Bowel Disease Care. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;12(6):403-406.

- Snapper SB. Very–Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;11(8):554-556.

- Zheng HB, de la Morena MT, Suskind DL. The Growing Need to Understand Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2021.675186