More than 7 million individuals around the globe suffer from one of the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs).1 Historically, IBD was considered a “Western” condition because the prevalence, or the number of people diagnosed with the condition, was highest in “Westernized” countries including the United States and some countries in Europe. In recent years, however, the incidence of IBD, or new cases being diagnosed, has skyrocketed globally alongside an increase in industrialization and expansion of dietary patterns like the Western or Standard American Diet.2,3 As IBD becomes more common around the world, it is essential for us to gain a deeper understanding of what IBD is, its symptoms and causes, and the potential for a cure.

The information below is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for medical care. Always consult your doctor if you are seeking medical advice, a diagnosis, or treatment for your condition.

What is Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

The inflammatory bowel diseases are idiopathic and chronic immune-mediated conditions including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), and microscopic colitis (MC) that affect all or specific parts of the gastrointestinal tract.4,5 A dysregulated immune response in the mucosal membrane of the GI tract results in inflammation of the tissue and subsequent symptoms and complications.6 “Idiopathic” essentially means that IBD is somewhat spontaneous—there is no single trigger or underlying cause that results in the development of IBD. IBD is also considered a chronic condition—while many treatments help address the symptoms of IBD, there is currently no true cure for inflammatory bowel disease. Both genetic and environmental factors appear to contribute to the onset of IBD. Therefore, both therapeutic and lifestyle interventions are often needed for the successful long-term management of this condition. Researchers are getting closer to understanding the cause of IBD and potential cures every single day, but for those of us suffering from IBD right now, scientific publications and breakthroughs are often inaccessible, difficult to understand, and muddied by a sea of misinformation about IBD online. Ultimately, the underlying causes, symptoms, and perfect treatment strategy for every case of IBD is unique.

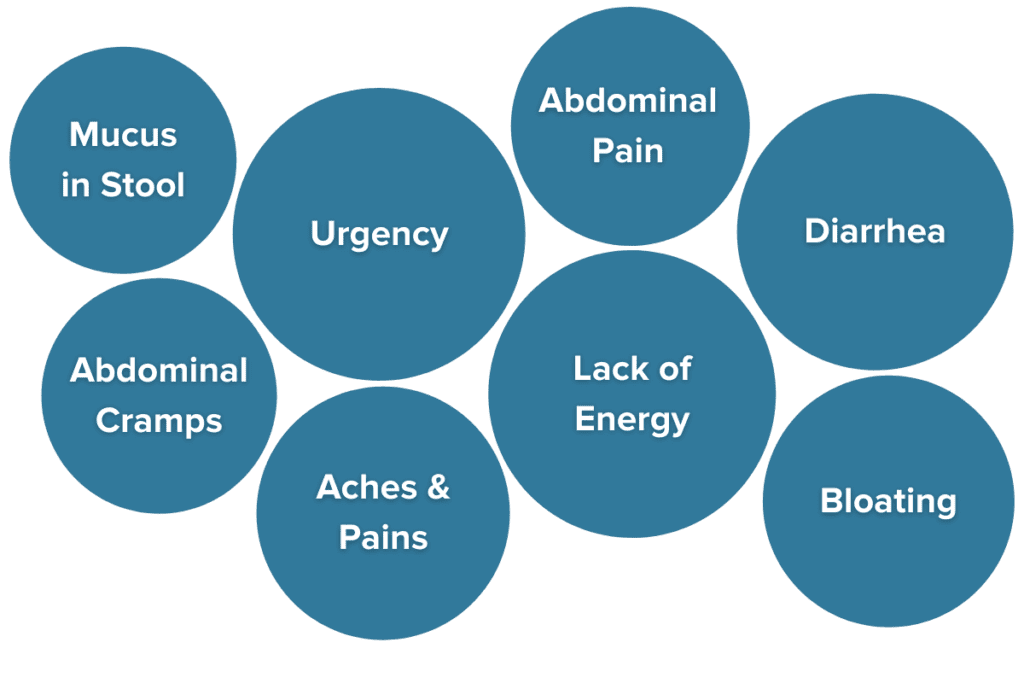

Symptoms of IBD

IBD severity can range from mild to extremely severe, even requiring hospitalization in some cases, depending on the subtype and individual. Common symptoms of IBD include:

- Frequent and urgent bowel movements (often over ten a day)

- Persistent diarrhea

- Blood and mucus are present in the stool (except in microscopic colitis)

- Painful cramping

- Whole-body aches and pains

- Unintentional weight loss and malnutrition

- Fatigue7,8

It is common for the symptoms of IBD to vary depending on the location and severity of inflammation. Bleeding, for example, is most common in UC due to the presence of ulcers in the colon. In MC, there is no ulceration or bleeding present but persistent diarrhea is common.

Symptoms of IBD become the most intense during “flares”—week- to month-long periods that involve the most severe IBD symptoms—and often cause patients to stay home, have frequent bowel movements, maintain liquid diets, and sometimes go to the ER for treatment.8,9 Extensive inflammation from UC or Crohn’s disease may become so severe that surgical intervention is required to remove the damaged intestine or colon. Beyond severe impacts on the gastrointestinal lining and GI symptoms to accompany it, many IBDers are surprised to learn that the effects of IBD reach far beyond the gut.

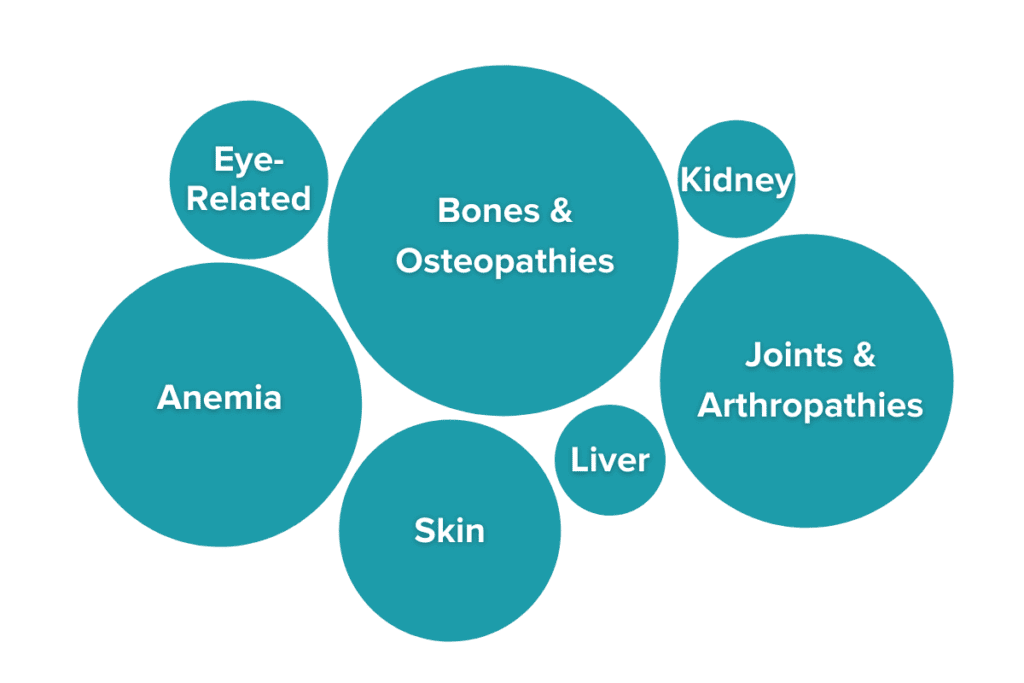

Extraintestinal Manifestations of IBD

UC and Crohn’s disease are not limited to the GI tract, as IBD has potent effects on many other areas of the body due to the effects of persistent, chronic inflammation. In fact, at least 47% of people with IBD have symptoms of IBD that present outside of their GI tract. These symptoms are known as extraintestinal manifestations of IBD (EIMs).10,11 Some of the most common EIMs include joint pain without swelling (experienced by over 35% of IBDers) and osteopenia and osteoporosis (experienced by 30%-60% of IBDers). Other EIMs may include pulmonary symptoms, anemia, ocular conditions like conjunctivitis or scleritis, or skin irritation.12 Extraintestinal manifestations can vary in severity, but severity frequently mirrors gastrointestinal disease activity. Many of these symptoms are resolved as the disease is treated, but others persist even when patients are in remission. Severe EIMs may require direct medical attention. Importantly, EIMs are not the same as complications of treatment, which are symptoms that arise as a side effect of medication use. The cluster of symptoms and unique pathology of each case helps doctors identify the specific subtype of IBD present in an individual.

Classifications of IBD

The two most common forms of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Less common IBDs include indeterminate colitis (IC) and microscopic colitis (MC). The IBDs are all chronic and recurring debilitating conditions that rapidly deteriorate the quality of life. Depending on the location of disease activity, the specific pathology of cells of the GI tract (how the intestinal tissue looks under a microscope), and disease severity, IBD may be classified into one of several subtypes.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerations and granularity in the colon are hallmark indicators of UC. The damage observed in ulcerative colitis is limited to the mucosal layer of the colon which is the most superficial layer of the intestinal lining. The inflammation in UC often spans large, continuous parts of the colon. Common symptoms of ulcerative colitis include the release of blood, mucus, or granulation tissue in stools from ulcers and abdominal bleeding. 13

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is characterized by the formation of granulomas, strictures, ulcers, and fistulas. CD primarily affects the terminal ileum (the juncture between the small and large intestine), but it can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the rectum. The inflammation in CD can affect all layers of the intestinal lining and is often patchy and noncontinuous.13 If Crohn’s disease activity is restricted to only the colon, it is classified as Crohn’s colitis (CC). If a physician cannot determine if a patient is suffering from UC or CC, a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis may be given. Symptoms of Crohn’s disease include diarrhea, bloody stools, malnutrition, abdominal pain, and weight loss.

Microscopic Colitis

Microscopic colitis is a (typically) milder form of IBD that affects only the colon. Inflammation cannot be seen with the naked eye but can be seen under a microscope, hence the name.14 There are two subtypes of microscopic colitis that are distinguished by what a doctor observes under the microscope:

- Collagenous colitis: presents as a thickening of the colonic lining caused by a build-up of collagen beneath the surface but without a build-up of lymphocytes.15

- Lymphocytic colitis: presents as a build-up of lymphocytes, a kind of immune cell, in the lining of the colon. There may or may not also be a thickened layer of collagen beneath the surface.16

Both forms of microscopic colitis primarily present with frequent, persistent diarrhea and abdominal pain while the other symptoms of IBD are less common. Because of this, medical treatments of microscopic colitis are primarily geared at controlling diarrhea.

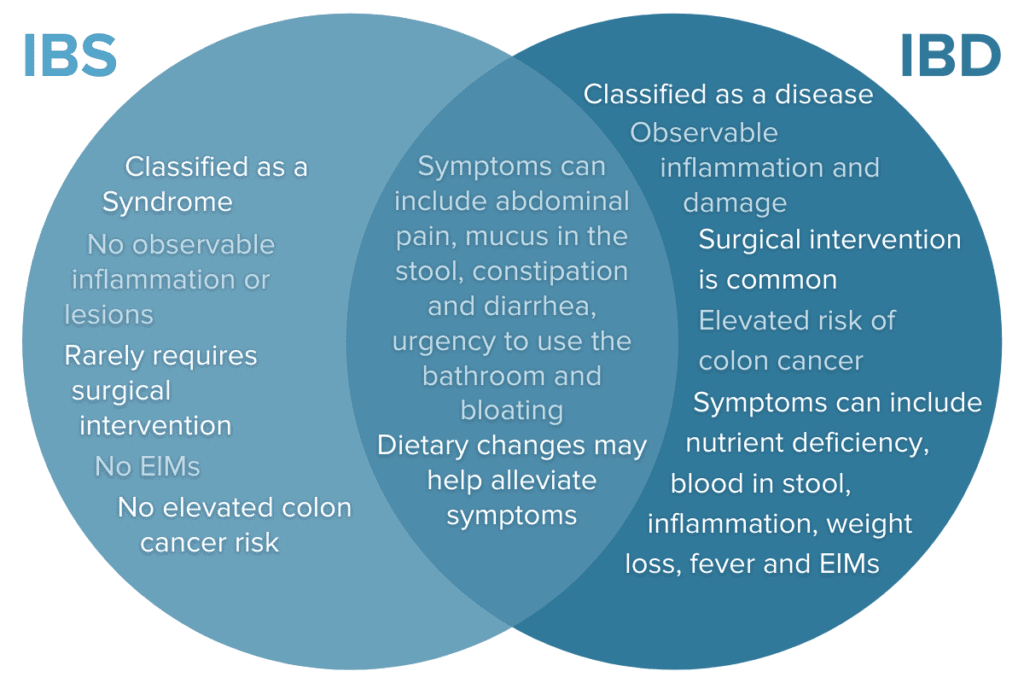

IBD vs. IBS

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is commonly confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). While IBS commonly presents with symptoms like abdominal pain and irregular bowel movements, IBS is not the same condition as IBD and it requires a unique treatment approach.17,18 In many ways, IBS is an even more mysterious condition and treatment strategies primarily include lifestyle and dietary interventions because the cause is not well understood.

Because IBD presents in so many unique ways with diverse constellations of symptoms, EIMs, and symptoms that overlap with other conditions like IBS, the diagnostic journey can be long and confusing. Let’s take a closer look at what it takes to receive an official IBD diagnosis.

Getting an IBD Diagnosis

Many IBD patients experience a lengthy diagnostic delay between the first appearance of symptoms and their official IBD diagnosis—often two years or more.19,20 To diagnose IBD accurately, physicians must rule out several other conditions in the process that have similar symptoms to IBD such as IBS and celiac disease.21 Additionally, physicians may rely on several techniques throughout the process, including colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, gastroscopy, video capsule endoscopy, MRI, CT, ultrasound, blood tests, and stool samples. Each additional diagnostic test utilized lengthens the diagnostic timeline. Getting an accurate diagnosis is imperative because the treatment approach varies between the different subtypes of IBD. Other factors that contribute to the diagnostic delay can include things like hormone cycles, especially in individuals with female sex hormones, which may complicate the presentation of symptoms. Let’s take a closer look at common tests, inflammatory markers, and comorbid conditions that can influence IBD diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tests and Markers for IBD

A wide variety of tests may be used to rule out comorbid conditions and accurately identify the location and severity of disease activity to give an accurate IBD diagnosis.21 Some commons tests are:

- Blood tests: Blood tests are used to diagnose and monitor IBD and to distinguish between IBD subtypes. Blood tests like C-reactive protein (CRP) and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) are non-specific, meaning they indicate a generally elevated state of inflammation rather than gut-specific inflammation. They can help identify that a person may have an inflammatory condition like IBD or an infection and can help rule out IBS.

- Stool tests: Stool tests like calprotectin22,23 and lactoferrin24 are used in the diagnosis of IBD as an initial indicator of intestinal inflammation and to check for the presence of blood in the stool. Stool tests are more specific to intestinal inflammation than blood tests and are also used to rule out conditions like IBS. Regular stool tests can also provide noninvasive monitoring data to indicate intestinal healing following treatment intervention.

- CT scans, MRIs, and X-rays: Imaging like CT scans, MRIs, and X-rays are used to obtain detailed visualizations of the GI tract to aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of IBD. DXA or DEXA scans are important assessments of bone density loss which can affect 30-60% of IBD patients. Medical imaging may also be helpful to identify complications like perforations, strictures, or fistulae.

- Endoscopy: Endoscopy is used to capture real images of the gastrointestinal tract to identify inflammation and screen for polyps, ulcers, and cancer. Endoscopy may also be used to collect tissue samples (biopsies) for further analysis. Biopsies are essential to rule out conditions like celiac disease or to identify microscopic colitis. Kinds of endoscopy include colonoscopy, upper endoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and video capsule endoscopy.

When used together, these diagnostic tests can pinpoint the location and severity of inflammation in the GI tract, home in on a specific IBD diagnosis, and rule out similar conditions.

Ruling out Similar Conditions

Many conditions ranging from acute infections to other chronic conditions can impact the GI tract and result in gastrointestinal symptoms like those seen in IBD. Some of the most common conditions that must be ruled out on the road to an IBD diagnosis are IBS, discussed above, and celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder where consumption of gluten leads to an auto-inflammatory response in the small intestine. Infections that must be ruled out often include Shigella, E. coli, C. diff, Salmonella, or Shiga. Infection with MAP (Mycobacterium avium, subspecies paratuberculosis), has been tied to increased risk of developing IBD, so doctors may also check for this.25,26

Ruling out similar conditions can be especially difficult when gastrointestinal symptoms are mild or absent (such as in between flares). Additionally, the presence of comorbid conditions (having more than one diagnosis at a time) can further complicate a doctor’s ability to accurately detect IBD. Having comorbid conditions may also influence which medication, diet, and lifestyle protocol are best suited for an individual.

Common Comorbidities

At least 78% of IBDers have at least one comorbid diagnosis.27 In many cases, having a comorbid condition may impact the best treatment strategy for IBD and the other condition.

- Arthritis: While arthropathies are a common EIM in people with IBD, many IBDers also have a diagnosis of arthritis. Unlike arthralgia, joint aches and pains not accompanied by inflammation, arthritis presents with inflammation.

- Depression and anxiety: Some sources suggest that as many as 30% of people with IBD also suffer from depression and/or anxiety. Many chronic conditions are unsurprisingly associated with rates of depression and anxiety that are more than twice that of the general population.

- PTSD: One study suggests that up to a third of IBDers experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following their IBD diagnosis. Symptoms of PTSD can include hypervigilance, intrusive memories, negative changes in thinking and mood, and more, and may dramatically impact an individual’s normal daily functioning and quality of life.

- Cancer: IBDers may be at increased risk for developing certain cancers, especially colorectal cancer. Risk is increased by disease severity, prolonged intestinal inflammation, and increased duration of active/uncontrolled disease. Certain medications for IBD are also associated with an increased risk of cancer.

- Celiac disease: Studies have indicated that celiac disease may be a risk factor for IBD and that celiac disease is more common in IBDers than in the general population.

Understanding Risk Factors for IBD

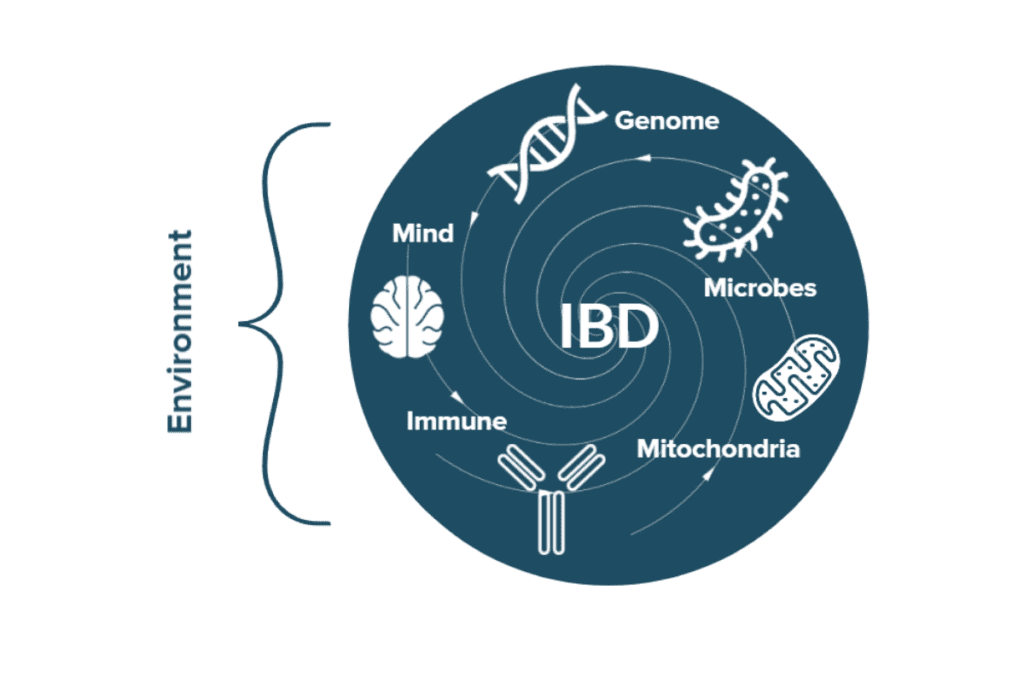

There is no single, definitive cause of IBD; rather, a perfect storm of genetic, biological, and environmental risk factors combine to result in each unique case.12,28–30 Genes, intestinal microbes, dietary patterns, antibiotic exposure, stress, lifestyle choices like exercise or smoking, the presence of comorbidities, and environmental exposures to pollution are just a few of the factors that have been shown to contribute to the perfect storm that ultimately causes IBD and affect the severity of IBD symptoms and treatment outcomes.

Hereditary Risk Factors for IBD: Genetics

One of the strongest risk factors for IBD is genetics—almost 200 genetic mutations have been correlated with increased risk for IBD.31 A child is potentially more than 9 times more likely to have UC when a sibling has UC and 26 times more likely to have Crohn’s when a sibling has Crohn’s.32,33 Because there is a greater risk of having IBD if a close relative also has it, it is understood that there is a strong hereditary (genetic) component to these conditions. However, there are also many cases where one sibling develops IBD and the other does not–even in identical twins! This means that environmental factors also play an important role, which we will discuss below.

Many of the genes linked to increased risk of IBD are involved in immune function and the maintenance of the intestinal lining. For example, a Crohn’s-associated mutation in the NOD2 gene (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2) gene prevents certain bacteria from being recognized for degradation and leads to immune dysregulation.34 Other mutations in Crohn’s are found in genes that control the innate immune response, modulate the degradation/recycling of biological waste (autophagy), and are associated with autoimmune disorders. Genes influencing UC risk are also frequently involved in inflammatory pathways such as regulators of the TNF-α inflammatory pathway.

Genetic Risk and Very Early Onset IBD (VEO-IBD)

A rare variant of IBD known as very-early onset IBD (VEO-IBD) affects children below the age of six and is more strongly linked to genetic variations. In VEO-IBD cases, there is a much more consistent and clear pattern of genetic mutations observed in patients that provides insight into the genetic factors at play in IBD pathology. For example, the mutations that appear to cause VEO-IBD disrupt immune homeostasis by affecting the epithelial barrier, its immune response to microbial pathogens, and T and B cell activation.

Importantly, many people with IBD only carry a small handful of the 200+ mutations linked to IBD risk, and carrying any one of these mutations does not guarantee that an individual will someday develop IBD. This is because of the strong role that environmental factors play in IBD.

Environmental Risk Factors for IBD: Epigenetics

In addition to genetic risk factors for IBD, there are almost infinite environmental factors that can impact the risk of developing IBD and impact the symptoms of IBD over time.35 Genetic risks provide a recipe for IBD while environmental factors provide the ingredients, equipment, and chefs to turn that recipe into a meal. The ability of the environment to control gene expression is known as epigenetics.

Humans have more than 20,000 genes, but not all of these genes are active simultaneously.36 Cooking every single recipe in a cookbook at once is not necessary. For example, most of us can appreciate that genes responsible for puberty and the soup of hormones that go along with it do not stay active during adulthood. Which genes are active at which times is largely a product of environmental influences. In this way, epigenetics plays a central role in IBD. Exposure to certain microbes, dietary habits, illnesses, stress, and more can all impact gene expression and activity and ultimately influence the risk of developing IBD and affect its symptoms and progression. Some of the many environmental factors known to impact IBD risk are:

| Risk Factor | Potential Influences on IBD |

| The Gut Microbiome | Dysbiosis of the gut microbiome can disrupt intestinal barrier integrity, trigger the immune response, affect nutrient processing, and more.37–39 Learn more about the link between the microbiome-gut-brain axis and IBD treatments. |

| Diet | Diets high in saturated fats, added sugars, certain processed ingredients, and low in fiber can contribute to inflammation, dysbiosis, and barrier function.40–42 Read more about the relationship between fiber and IBD. |

| Immune Factors | Antibiotic use can contribute to intestinal dysbiosis and immune activity.43 Infection with certain environmental pathogens may increase the risk of developing IBD.26,44 Breastfeeding may promote stronger immune systems and balanced microbiomes in children.45 |

| Mitochondria | Some studies suggest that dysfunction in the powerhouse of the cell may disrupt immune function, barrier integrity, and more.46 |

| Stress | Additionally, GI conditions like IBD are more common in individuals suffering from stress-related disorders such as anxiety and PTSD. Stress may increase inflammation, cause dysbiosis, and increase barrier permeability.47,48 Learn about the Surprising Way Psychedelics may Help with Stress and IBD. |

| Lifestyle Choices | Smoking,49 use of hormonal birth control,30 and other lifestyle factors can make at-risk individuals more likely to develop IBD. Read more about the role of hormonal birth control in IBD here. |

| Physical Environment | Environmental factors like regional climate and sun exposure may also influence IBD risk.50,51 Environmental factors may impact the immune system, microbiota, or availability of important micronutrients like vitamin D. |

No single one of these factors, genetic or environmental, has been shown to cause IBD every single time. Two people could possess completely identical risk profiles for IBD, but only one of them will go on to develop the disease. Someone may have many risk factors and extremely mild symptoms, while someone else may have very few risk factors and experience severe symptoms. Likewise, someone may possess a perfect storm of protective factors and still go on to develop IBD. Understanding each individual’s unique profile of risks, however, can help better inform treatment decisions and inspire the development of an individualized IBD Remission Master Plan.

The Underlying Cause of IBD

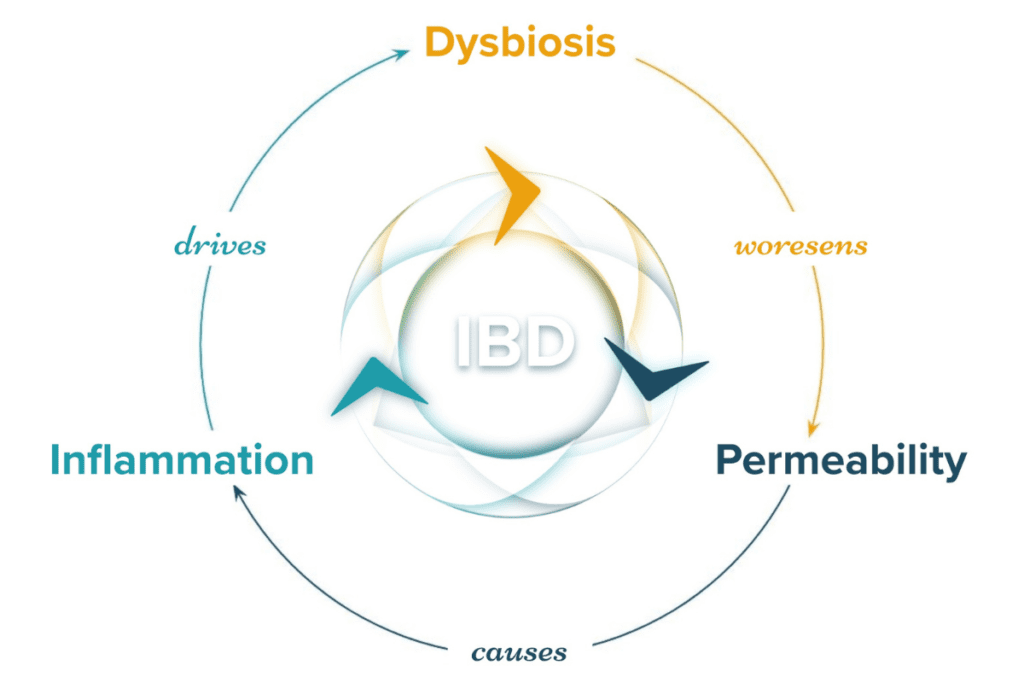

IBD is classically considered an idiopathic or spontaneous condition, meaning there is no defined root cause or trigger. Taking a closer look at the risk factors for IBD, the symptoms of IBD, and the biology behind IBD elucidates three key mechanisms that are at play.

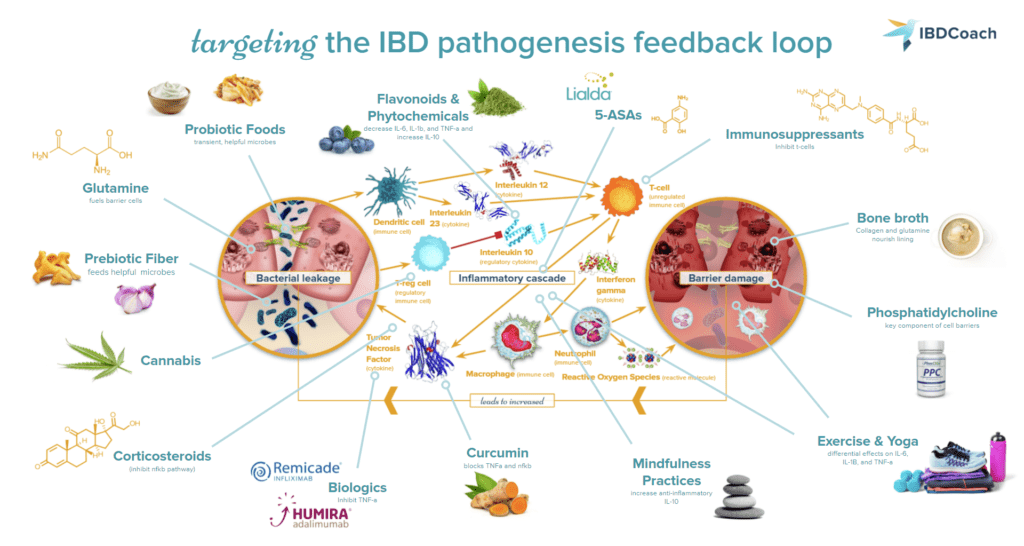

The Three Mechanisms of IBD

In IBD, we observe the breakdown of the intestinal barrier (comprising gut cells called enterocytes) which leads to increased permeability and allows food particles and bacterial organisms to slip through. Cells of the immune system called macrophages and neutrophils, in their attempt to protect tissue from infection by the bacteria, inadvertently cause devastating damage to the lining of the gut. This inflammatory state disrupts the inhabitants of the gut microbiome and causes a state of imbalance known as microbial dysbiosis, furthering the cycle of increased intestinal permeability and immune reactivity.6,52 Microbial dysbiosis, intestinal permeability, and inflammation are the foundational mechanisms that must be addressed in IBD. Scientific evidence has repeatedly indicated these three mechanisms as driving forces in IBD and that is why they are the core of the IBDCoach program.

Mechanism 1: Inflammation

As bacterial organisms and other luminal particulates leak across the epithelial membrane into the lamina propria, the immune system mounts a powerful response involving multiple cytokines like TNF and white blood cells like macrophages and neutrophils. Stopping the inflammation becomes step one on the road to remission.53

Mechanism 2: Dysbiosis

Certain microbiome profiles have been consistently correlated with IBD, with even distinct differences observed between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). The variety and abundance of specific bacterial and fungal organisms are in stark contrast to that of healthy controls.37–39 A dysbiotic microbiome can fuel the inflammatory cycle, disrupt gut function, and disrupt intestinal barrier integrity. Frontline medical interventions for IBD do not address the microbiome, even though this seems anomalous with the emerging evidence. Balancing the microbiome becomes step two on the road to remission.

Read More About Dysbiosis and IBD Here

Mechanism 3: Intestinal Permeability

In cases of IBD, intestinal barrier permeability is increased which allows bacterial particulates to leak through the lining to trigger a runaway immune cycle.53,54 Repairing the barrier is the mechanism least addressed by current frontline medication interventions, but by stopping the inflammation and fueling a balanced gut microbiome, we can bolster intestinal barrier integrity. Repairing the barrier becomes step three on the road to remission.

In reality, the three mechanisms of IBD are a part of an intimately connected system where no single component stands alone. Working toward disrupting one mechanism to begin the process of healing from IBD will also begin to disrupt the others. Balancing the microbiome, for example, can pave the way for repairing the gut barrier because microbes help feed strong intestinal cells. Likewise, one mechanism spiraling out of control can cause the others to worsen. Rising levels of inflammation due to stress, for example, can cause the balance of the microbiome to shift and increase intestinal permeability. Overcoming IBD requires a carefully crafted protocol that successfully addresses all three mechanisms of IBD to break the cycle and promote healing and robust remission.

What is Remission from IBD?

One of the most common questions that someone new to IBD will ask is, “What is the cure for IBD?”

Medically speaking, a cure is a treatment that permanently resolves an ailment or condition. At this point in time, a cure for inflammatory bowel disease has not yet been discovered. IBD is a relapsing and remitting condition that is present for life. But that does not mean an IBD diagnosis is hopeless. Many IBDers can achieve remission, a deep state of disease inactivity that can last for many years.55 For some IBDers, the experience of remission often feels as though they are “cured,” but it is important to understand that “flares” (periods of heightened disease activity) and recurrence of disease activity are always possible.

Remission looks different for everyone, but it is often described by physicians or patients in several different ways:

- Clinical or Symptomatic Remission: the subjective experience of having no symptoms of active Crohn’s or UC for a period of time.

- Endoscopic Remission: no signs of IBD or active inflammation are observed during an endoscopic procedure like a colonoscopy.

- Histologic Remission: no signs of IBD or active inflammation are observed in biopsies taken from the affected area of the GI tract.

- Biochemical Remission: inflammatory markers used to monitor IBD indicate no active inflammation.

Understanding the differences in these different kinds of remission is essential to assess each unique situation. In some cases, a patient may feel that they are in clinical remission, but their doctor still observes signs of inflammation on a colonoscopy, biopsy, or blood test. While the feeling of symptomatic relief is worth celebrating, the lack of endoscopic, histologic, or biochemical remission could be an early warning sign worth paying attention to.

For many people, true remission is often more than what either clinical or symptomatic remission can encompass. Remission can mean feeling comfortable in your body again, remission can mean feeling like yourself again, remission can mean feeling “normal” for the first time in a long time. No biochemical marker or biopsy can possibly capture the true scope of what remission means to a person with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis, or indeterminate colitis.

Remission from Inflammatory Bowel Disease is not a destination — it’s a way of life. You will not simply arrive there. Instead, you will live and breathe remission every day. Remission requires planning and awareness, strength and grit, a pronounced ability to adapt within new and challenging contexts and circumstances. Remission is like surfing down the face of a big wave or moving with the agility of a hummingbird. It’s a state of flow with my natural surroundings where harmonious freedom meets refreshing control – no longer resisting or fighting nature’s power, but instead harnessing her energy for our mutual, symbiotic benefit.

Achieving remission from IBD does not require magic. It instead demands remarkable persistence and a new state of mind. This change will allow you to engage reasonable strategies based on scientific discovery and evidence. You will begin to reconcile and observe the delicate interconnection of human biology to the environment you inhabit. You will acknowledge yourself as an individual with unique life circumstances, needs, and dreams who will always require tailored interventions designed specifically for you and by you. At this time remission will cease to be a far-off, unattainable destination — it will become my way of life.

Andrew Kornfeld

Frontline Treatments for IBD

Achieving remission from Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and microscopic colitis most often requires a personalized combination of medications, dietary changes, and lifestyle adjustments. Because every case of IBD is different and every IBDer has their own unique constellation of IBD risk factors, there is no one-size-fits-all treatment for IBD. Some of the most common treatment strategies that fit into a robust IBD protocol are:

- Medications for IBD: Pharmaceutical medications are one of the most powerful tools in the IBD tool belt for getting inflammation under control to lay the foundation for healing in the GI tract. In general, medications for IBD may act either in the short term to reduce inflammation or in the long term to quiet the overactive immune system and prevent flares. Common IBD medications include:9

- Corticosteroids:

- 5-ASAs:

- Immunomodulators:

- Biologics:

- Small Molecule Therapies:

- Diets for IBD: A dietary strategy is one of the next most important components of a robust and well-rounded IBD protocol. Diet in IBD is an individual matter, and the fact remains that a wide range of dietary strategies can be employed to yield benefits in IBD.56,57 Some of the most common dietary strategies recommended for IBD include the specific carbohydrate diet (SCD), the IBD anti-inflammatory diet (IBD-AID), and the autoimmune protocol (AIP). There is no one-size-fits-all best IBD diet, and many IBDers find that some combination of the aforementioned strategies tailored to their unique needs (especially when employed in combination with a tailored medication protocol) often works best.

- Supplements for IBD: Supplements, vitamins, and herbs are compounds intended to be added to an existing health protocol to improve, or “supplement”, intake of certain nutrients or beneficial compounds. This broad category can include vitamins, minerals, proteins and amino acids, antioxidants, herbs, plants, fungi, and other biological molecules. Supplements are not miracle treatments. Instead, supplements should be incorporated as part of a holistic health protocol to boost the effectiveness of other strategies.58

- Lifestyle Changes for IBD: Lifestyle changes can be an easy addition to your routine to help you feel better now. Prioritizing better mindfulness practices, exercise, sleep, and hydration can dramatically improve IBD outcomes.59–62 Establishing new routines and committing to small changes can be a huge first step.

- Mindset Changes for IBD: IBD is a chronic condition and it takes time to heal and recover. Failures happen, flares happen, and setbacks happen. Embracing a growth mindset and meeting these challenges and setbacks with the determination to overcome them in a strategic and organized fashion will help propel you forward on the road to remission. Mindset has a positive impact on treatment outcomes for a wide variety of conditions, and IBD is no exception to this pattern.61,63,64

While every perfect IBD protocol is different, there seems to be a universal trend that no one strategy alone is sufficient to promote and maintain remission from IBD. Just like IBD results from a combination of risk factors, remission is the sum of a rounded, individualized protocol involving many angles of attack.

Summary: What is IBD?

In this article, we’ve learned that IBD is a cluster of chronic gastrointestinal conditions including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and microscopic colitis that impact well over seven million individuals around the world. While the root cause of IBD is not fully understood, a complicated collection of genetic and environmental risk factors seem to fuel the development of IBD and may increase the severity of IBD symptoms. To overcome the symptoms of IBD and promote healing of the GI tract to achieve remission, a well-rounded treatment protocol including medications, dietary changes, and lifestyle changes is needed.

Most importantly, no two cases of IBD are alike. Each person with IBD has their own unique cluster of risk factors, symptoms of IBD, idea of what remission means to them, and approach to treatment. All IBD perspectives and journeys are valid, and no IBDer should ever be shamed for their treatment goals and decisions or feel pressured to conform to the “best” treatment strategy. It is common to stumble upon dietary strategies or supplements online that promise to be cure-alls for IBD, but remember this: if one dietary change or supplement could cure IBD, IBD would actually boil down to a simple nutrient or mineral deficiency. Everything we know about IBD biology and all of the complicated mechanisms that fuel the development and progression of this chronic condition shows that this is not the case. The road to remission is long, winding, and can be full of ups and downs. There is no easy way to the end, but if you listen to your body, advocate for your needs, and put in the work to find a protocol that works for your unique needs and goals, you can enjoy the benefits of a long-lasting, deep remission.

Need help getting started? Sign up for an Admissions Call with IBDCoach and find out how we can help you build your personalized Remission Master Plan for Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis or microscopic colitis.

Reserve Your Admissions Call Today!

This is the first post of a three-part series on everything you need to know about IBD. Our second post takes a deeper dive into the treatments for IBD and explores what makes these treatments effective at alleviating the symptoms of IBD by addressing all three mechanisms of IBD. Read more here.

Our third post takes an intimate look at living life with IBD and reveals some of the often-overlooked facets of living with a chronic health condition. We’ll take a look at the psychological toll of coping with IBD, life in remission, and what to expect down the road as you continue to live with IBD. Read more here.

- Alatab, S., et al. The Global, Regional, and National Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 5 (1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30333-4.

- Kaplan, G. G.; Windsor, J. W. The Four Epidemiological Stages in the Global Evolution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18 (1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x.

- Windsor, J. W.; Kaplan, G. G. Evolving Epidemiology of IBD. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2019, 21 (8), 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-019-0705-6.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – Symptoms and causes https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353315 (accessed 2021 -11 -05).

- Microscopic colitis – Symptoms and causes https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/microscopic-colitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351478 (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Ramos, G. P.; Papadakis, K. A. Mechanisms of Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019, 94 (1), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.013.

- Farrell, D.; McCarthy, G.; Savage, E. Self-Reported Symptom Burden in Individuals with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016, 10 (3), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv218.

- Ballou, S.; Hirsch, W.; Singh, P.; Rangan, V.; Nee, J.; Iturrino, J.; Sommers, T.; Zubiago, J.; Sengupta, N.; Bollom, A.; Jones, M.; Moss, A. C.; Flier, S. N.; Cheifetz, A. S.; Lembo, A. Emergency Department Utilization for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States from 2006–2014. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018, 47 (7), 913–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14551.

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8.

- Levine, J. S.; Burakoff, R. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011, 7 (4), 235–241.

- Extraintestinal Complications of IBD https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd/extraintestinal-complications-ibd (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Vavricka, S. R.; Schoepfer, A.; Scharl, M.; Lakatos, P. L.; Navarini, A.; Rogler, G. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2015, 21 (8), 1982–1992. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000392.

- CDC -What is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)? – Inflammatory Bowel Disease – Division of Population Health https://www.cdc.gov/ibd/what-is-IBD.htm (accessed 2021 -11 -05).

- Boland, K.; Nguyen, G. C. Microscopic Colitis: A Review of Collagenous and Lymphocytic Colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017, 13 (11), 671–677.

- Collagenous colitis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6135/collagenous-colitis#:~:text=In%20all%20forms%20of%20microscopic,suddenly%20or%20worsen%20over%20time. (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Lymphocytic colitis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/6939/lymphocytic-colitis (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- What’s the difference between IBS and IBD? https://www.cedars-sinai.org/blog/is-it-ibs-or-ibd.html (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- IBS vs IBD https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd/ibs-vs-ibd (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Nguyen, V. Q.; Jiang, D.; Hoffman, S. N.; Guntaka, S.; Mays, J. L.; Wang, A.; Gomes, J.; Sorrentino, D. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Associated Factors on Clinical Outcomes in a U.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 2017, 23 (10), 1825–1831. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000001257.

- Lee, D.; Koo, J. S.; Choe, J. W.; Suh, S. J.; Kim, S. Y.; Hyun, J. J.; Jung, S. W.; Jung, Y. K.; Yim, H. J.; Lee, S. W. Diagnostic Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Increases the Risk of Intestinal Surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23 (35), 6474–6481. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6474.

- How is IBD Diagnosed? https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/what-is-ibd/diagnosing-ibd (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Bjarnason, I. The Use of Fecal Calprotectin in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2017, 13 (1), 53–56.

- Khaki-Khatibi, F.; Qujeq, D.; Kashifard, M.; Moein, S.; Maniati, M.; Vaghari-Tabari, M. Calprotectin in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Chim Acta 2020, 510, 556–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.025.

- Dai, J.; Liu, W.-Z.; Zhao, Y.-P.; Hu, Y.-B.; Ge, Z.-Z. Relationship between Fecal Lactoferrin and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007, 42 (12), 1440–1444. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520701427094.

- IBD Mimics: Most Common Conditions Misdiagnosed as IBD https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/science-and-professionals/education-resources/ibd-mimics-most-common-conditions-misdiagnosed-ibd (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Pierce, E. S. Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Is Mycobacterium Avium Subspecies Paratuberculosis the Common Villain? Gut Pathog 2010, 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-4749-2-21.

- Bähler, C.; Schoepfer, A. M.; Vavricka, S. R.; Brüngger, B.; Reich, O. Chronic Comorbidities Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prevalence and Impact on Healthcare Costs in Switzerland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 29 (8), 916–925. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000000891.

- Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 12 (4), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2015.34.

- Carreras-Torres, R.; Ibáñez-Sanz, G.; Obón-Santacana, M.; Duell, E. J.; Moreno, V. Identifying Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Sci Rep 2020, 10 (1), 19273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76361-2.

- Cornish, J. A.; Tan, E.; Simillis, C.; Clark, S. K.; Teare, J.; Tekkis, P. P. The Risk of Oral Contraceptives in the Etiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008, 103 (9), 2394–2400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02064.x.

- Cleynen, I.; Boucher, G.; Jostins, L.; Schumm, L. P.; Zeissig, S.; Ahmad, T.; Andersen, V.; Andrews, J. M.; Annese, V.; Brand, S.; Brant, S. R.; Cho, J. H.; Daly, M. J.; Dubinsky, M.; Duerr, R. H.; Ferguson, L. R.; Franke, A.; Gearry, R. B.; Goyette, P.; Hakonarson, H.; Halfvarson, J.; Hov, J. R.; Huang, H.; Kennedy, N. A.; Kupcinskas, L.; Lawrance, I. C.; Lee, J. C.; Satsangi, J.; Schreiber, S.; Théâtre, E.; van der Meulen-de Jong, A. E.; Weersma, R. K.; Wilson, D. C.; Parkes, M.; Vermeire, S.; Rioux, J. D.; Mansfield, J.; Silverberg, M. S.; Radford-Smith, G.; McGovern, D. P. B.; Barrett, J. C.; Lees, C. W. Inherited Determinants of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Phenotypes: A Genetic Association Study. The Lancet 2016, 387 (10014), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00465-1.

- Gordon, H.; Trier Moller, F.; Andersen, V.; Harbord, M. Heritability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From the First Twin Study to Genome-Wide Association Studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015, 21 (6), 1428–1434. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000393.

- Probert, C. S.; Jayanthi, V.; Hughes, A. O.; Thompson, J. R.; Wicks, A. C.; Mayberry, J. F. Prevalence and Family Risk of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: An Epidemiological Study among Europeans and South Asians in Leicestershire. Gut 1993, 34 (11), 1547–1551. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.11.1547.

- Sidiq, T.; Yoshihama, S.; Downs, I.; Kobayashi, K. S. Nod2: A Critical Regulator of Ileal Microbiota and Crohn’s Disease. Frontiers in Immunology 2016, 7.

- Molodecky, N. A.; Kaplan, G. G. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2010, 6 (5), 339–346.

- What is a gene?: MedlinePlus Genetics https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/basics/gene/ (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Glassner, K. L.; Abraham, B. P.; Quigley, E. M. M. The Microbiome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020, 145 (1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.003.

- Khan, I.; Ullah, N.; Zha, L.; Bai, Y.; Khan, A.; Zhao, T.; Che, T.; Zhang, C. Alteration of Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Cause or Consequence? IBD Treatment Targeting the Gut Microbiome. Pathogens 2019, 8 (3), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens8030126.

- Sultan, S.; El-Mowafy, M.; Elgaml, A.; Ahmed, T. A. E.; Hassan, H.; Mottawea, W. Metabolic Influences of Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 715506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.715506.

- Lo, C.-H.; Lochhead, P.; Khalili, H.; Song, M.; Tabung, F. K.; Burke, K. E.; Richter, J. M.; Giovannucci, E. L.; Chan, A. T.; Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Dietary Inflammatory Potential and Risk of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 159 (3), 873-883.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.011.

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Komatsu, M. Westernized Diet Is the Most Ubiquitous Environmental Factor in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Perm J 2019, 23, 18–107. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-107.

- Armstrong, H.; Mander, I.; Zhang, Z.; Armstrong, D.; Wine, E. Not All Fibers Are Born Equal; Variable Response to Dietary Fiber Subtypes in IBD. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2021, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2020.620189.

- Nguyen, L. H.; Örtqvist, A. K.; Cao, Y.; Simon, T. G.; Roelstraete, B.; Song, M.; Joshi, A. D.; Staller, K.; Chan, A. T.; Khalili, H.; Olén, O.; Ludvigsson, J. F. Antibiotic Use and the Development of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A National Case-Control Study in Sweden. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 5 (11), 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30267-3.

- Zamani, S.; Zali, M. R.; Aghdaei, H. A.; Sechi, L. A.; Niegowska, M.; Caggiu, E.; Keshavarz, R.; Mosavari, N.; Feizabadi, M. M. Mycobacterium Avium Subsp. Paratuberculosis and Associated Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Iranian Patients. Gut Pathogens 2017, 9 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-016-0151-z.

- Xu, L.; Lochhead, P.; Ko, Y.; Claggett, B.; Leong, R. W.; Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Breastfeeding and the Risk of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017, 46 (9), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14291.

- Novak, E. A.; Mollen, K. P. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Cell Dev Biol 2015, 3, 62. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2015.00062.

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Xie, R.; Wang, B.; Jiang, K.; Cao, H. Stress Triggers Flare of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adults. Front Pediatr 2019, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00432.

- Mawdsley, J. E.; Rampton, D. S. Psychological Stress in IBD: New Insights into Pathogenic and Therapeutic Implications. Gut 2005, 54 (10), 1481–1491. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2005.064261.

- Rosenfeld, G.; Bressler, B. The Truth about Cigarette Smoking and the Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2012, 107 (9), 1407–1408. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2012.190.

- Ng, S. C.; Bernstein, C. N.; Vatn, M. H.; Lakatos, P. L.; Loftus, E. V.; Tysk, C.; O’Morain, C.; Moum, B.; Colombel, J.-F.; Disease (IOIBD), on behalf of the E. and N. H. T. F. of the I. O. of I. B. Geographical Variability and Environmental Risk Factors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 2013, 62 (4), 630–649. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661.

- Fletcher, J.; Cooper, S. C.; Ghosh, S.; Hewison, M. The Role of Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanism to Management. Nutrients 2019, 11 (5), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051019.

- de Mattos, B. R. R.; Garcia, M. P. G.; Nogueira, J. B.; Paiatto, L. N.; Albuquerque, C. G.; Souza, C. L.; Fernandes, L. G. R.; Tamashiro, W. M. da S. C.; Simioni, P. U. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Overview of Immune Mechanisms and Biological Treatments. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 493012. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/493012.

- Matricon, J.; Barnich, N.; Ardid, D. Immunopathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Self Nonself 2010, 1 (4), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.4161/self.1.4.13560.

- Michielan, A.; D’Incà, R. Intestinal Permeability in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenesis, Clinical Evaluation, and Therapy of Leaky Gut. Mediators Inflamm 2015, 2015, 628157. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/628157.

- Crohn’s Disease: Get Into Remission and Stay There https://www.webmd.com/ibd-crohns-disease/crohns-disease/crohns-remission (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Green, N.; Miller, T.; Suskind, D.; Lee, D. A Review of Dietary Therapy for IBD and a Vision for the Future. Nutrients 2019, 11 (5), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11050947.

- Special IBD Diets https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/diet-and-nutrition/special-ibd-diets (accessed 2021 -10 -02).

- Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation https://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/diet-and-nutrition/supplementation (accessed 2022 -03 -21).

- Kinnucan, J. A.; Rubin, D. T.; Ali, T. Sleep and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Exploring the Relationship Between Sleep Disturbances and Inflammation. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013, 9 (11), 718–727.

- Bilski, J.; Brzozowski, B.; Mazur-Bialy, A.; Sliwowski, Z.; Brzozowski, T. The Role of Physical Exercise in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/429031.

- Ewais, T.; Begun, J.; Kenny, M.; Rickett, K.; Hay, K.; Ajilchi, B.; Kisely, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mindfulness Based Interventions and Yoga in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2019, 116, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.010.

- Wilke, E.; Reindl, W.; Thomann, P. A.; Ebert, M. P.; Wuestenberg, T.; Thomann, A. K. Effects of Yoga in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and on Frequent IBD-Associated Extraintestinal Symptoms like Fatigue and Depression. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 2021, 45, 101465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101465.

- Sirois, F. M.; Molnar, D. S.; Hirsch, J. K. Self-Compassion, Stress, and Coping in the Context of Chronic Illness. Self and Identity 2015, 14 (3), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.996249.

- Ewais, T.; Begun, J.; Kenny, M.; Hay, K.; Houldin, E.; Chuang, K.-H.; Tefay, M.; Kisely, S. Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy for Youth with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Depression – Findings from a Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2021, 149, 110594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110594.